Lord C-J at OECD : Mixed evidence on UK AI Governance

I recently attended a meeting of the OECD Global Parliamentary Network Group on Artificial Intelligence and spoke on UK developments during a session on Innovating in AI Legislation

It seems a long time since we all got together in person-what a pleasure! And such a pleasure to follow Eva. I am a huge admirer of what the EU have done in the AI space. I think we are all now beginning to be aware of the importance of digital media and the importance of AI and algorithms in our lives both positive and negative.Inevitably what I say is mainly focused on what we are doing in the UK but I hope it will have relevance in other jurisdictions.

The good news is that despite ( just a few!) changes in government or the pandemic UK government action on AI governance has been moving forward.

The UK’s National AI strategy - A ten-year plan for UK investment in and support of AI-was published in September 2021. It promised an AI Governance White Paper this year. In an AI policy paper and Action Plan published this July the Government then set out its emerging proposals for regulating AI in a policy consultation paper in which it committed to develop “a pro-innovation national position on governing and regulating AI.” This will be used to develop the White paper which may yet emerge this year.

Their approach would be “Establishing clear, innovation-friendly and flexible approaches to regulating AI will be core to achieving our ambition to unleash growth and innovation while safeguarding our fundamental values and keeping people safe and secure. …….drive business confidence,promote investment, boost public trust and ultimately drive productivity across the economy.” Fine words but we now have some more detailed clues as to the future of regulation of AI in the UK.

As regards categorising AI rather than working to a clear definition of AI determining what falls within scope, which is the approach taken by the EU Regulation, the UK has elected to follow an approach that instead sets out the core principles of AI which allows regulators to develop their own sector-specific definitions to meet the evolving nature of AI as technology advances.

In a surprising admission the policy paper does acknowledge that a context-driven approach may lead to less uniformity between regulators and may cause confusion and apprehension for stakeholders who will potentially need to consider the regime of multiple regulators as well as the measures required to be taken to deal with extra-territorial regimes, such as the EU Regulation.

To facilitate its ‘pro-innovation’ approach, the UK Government however has proposed several early cross-sectoral and overarching principles which build on the OECD ‘Principles on Artificial Intelligence’ . These principles will be interpreted and implemented by regulators within the context of the environment they oversee and would therefore be flexible to interpretation. This call for views and evidence closed on 26 September so we shall see what emerges in the White paper probably not this year!!

As a result of this context-driven approach the regulators in different sectors are going to take centre stage. So it is timely that 4 of our key regulators the ICO OFCOM CMA FCA have got together under a new Digital Regulators Cooperation Forum to pool expertise in this field. This includes sandboxing and input from a variety of expert institutes such as the Alan Turing Institute on areas such as risk assessment, AI, audit, digital design frameworks and standards digital advertising and horizon scanning

The policy paper in turn has led to the launch this October of the interactive hub platform AI Standards Hub led by the Alan Turing institute with the support of the British Standards Institution and National Physical Laboratory which will provide users across industry, academia and regulators with practical tools and educational materials to effectively use and shape AI technical standards.

All this represents action but while the National AI strategy paper of last September does talk about public trust and the need for trustworthy AI,my view is that it needs to be reflected in how we regulate. In the face of the need to retain public trust we need to be clear, above all, that regulation is not necessarily the enemy of innovation, it can in fact be the stimulus and be the key to gaining and retaining public trust around digital technology and its adoption so we can realise the benefits and minimise the risks.

International harmonization is in my view essential if we are to see developers able to commercialize their products on a global basis assured that they are adhering to common standards of regulation. One of my regrets is that the UK government unlike our technical experts doesn’t devote enough attention to positive collaboration in a number of international AI fora such as the Council of Europe, UNESCO And the OECD

But the UK IS playing an active part in GPAI serviced by the OECD which is beginning to deliver some interesting output particularly in respect of the workplace. I hope too that when the White Paper does emerge that there is recognition that we need a considerable degree of convergence between ourselves the EU, members of the COE and the OECD in particular, for the benefit of our developers and cross border business that recognizes that a risk based form of horizontal rather than purely sectoral regulation is required.

Above all this means agreeing on standards for risk and impact assessments alongside tools for audit and continuous monitoring for higher risk applications..That way I believe we can draw the US into the fold as well.

Other aspects of policy where I do NOT believe we are heading in the right direction however are

Data :The government’s “Data A New Direction” consultation has led to a new Data Protection bill. Despite little appetite in the business or the research communities they are proposing major changes to the GDPR post Brexit including not requiring firms to have a DPO or DPIA. All this is likely to impact on the precious EU Adequacy Decision which was made in June 21 and is meant to last for 4 years.

IP: Our Intellectual Property Office too is currently grappling with issues relating to IP created by AI . Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property: copyright and patents consultation closed January 2022 and now has recommended changes to text and data mining exemption which has been very widely criticised by the creative industries, publishers etc.

In addition although the UK Government has recognized the need for any amount of guidance for public sector organizations there is no central and local government compliance mechanism and little transparency in the form of a public register of use of automated decision making.

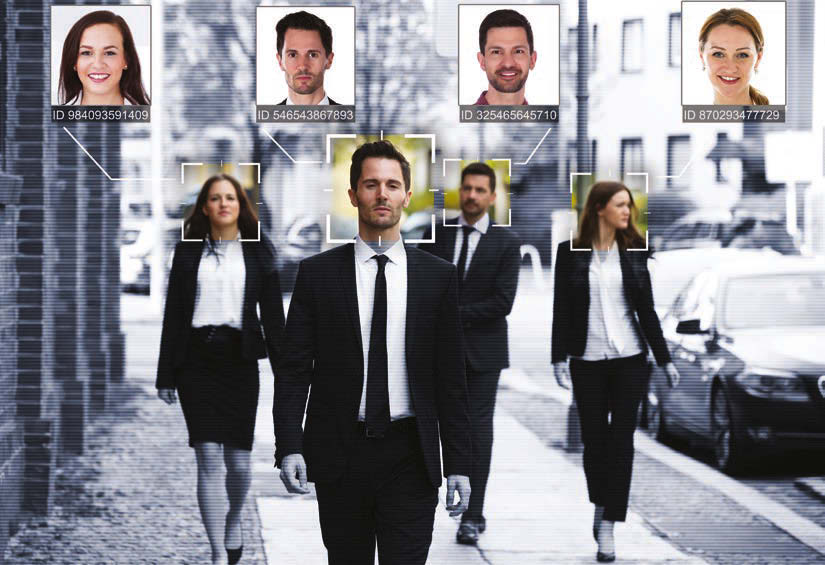

We also, despite the efforts of Parliamentarians and organisations such as the Ada Lovelace Institute, have no recognition at all that regulation for intrusive AI technology such as live facial recognition is needed.

We are still having a major debate on the deployment over live facial recognition technology -the use of biometrics and AI - in policing, schools and in criminal justice recently. Many of us have real concern that we are approaching the surveillance state.

In addition there is little appetite in government to ensure that our employment laws protect the increasing number of workers in the gig economy whose lives can be ruled by algorithm without redress.

So our government is engaged in a great deal of activity, the question as ever is whether it is fast or focused enough and whether the objectives such as achieving trustworthy AI and harmonized international standards are going to be achieved through the actions being taken so far. As you’ve heard today, I believe the evidence of success is still mixed! I still have quite a political shopping list!

How to Make the UK the Best Place in the World for Artificial Intelligence.

I recently gave a talk at a meeting of members of The Entrepreneurs Network. This is slightly expanded version.

It's pleasure to be in Entrepreneurial company tonight

The Truss/Kwarteng paradise of Britannia Unchained to unleash growth, growth growth has been showed up for what it it was. It didn’t outlast a lettuce. I hope that with Rishi Sunak as PM we are at the end of the magical thinking era.

I am always an optimist but I look forward to hearing whether you agree with Guy Hands who thinks we’re going to be the sick man of Europe.

So I’m not going to talk at you too long and I’m certainly not going to get into detailed expenditure or taxation proposals! That would be bound to get me into trouble.

And the first thing to remember is that policy is all very well but its results that matter and government can be the graveyard for good ideas, innovation and enterprise. You only have to read Kate Bingham’s recent book Long Shot to understand how bureaucratic process can so easily be a killer of good intentions and effective outcomes.

The second is that we are in my view fighting a combination of factors including the effects of COVID Brexit, Austerity, and political instability to put it mildly. Mathew Syed in his Sunday Times column headlined that an “Irrational faith in the providence of Brexit has trapped adherents in cognitive dissonance and denial” . We need a frank appraisal of the impact of Brexit and fix the consequences where we can.

So our economic circumstances really do require prioritisation and clear thinking.

What I would like to do is throw out a few thoughts for discussion on where the focus of government policy should be in order to grow our tech sector in general and AI development and adoption in particular.

The challenges include.

- how can we convert academic success into entrepreneurship?

- How can we increase the speed of business adoption of AI tech in the UK?

- How can we best guard against future harms that AI could bring?

I am saying all this of course in the light of the Government’s grand 10 year plan “Make Britain a global AI superpower” published a year ago.

Let’s briefly consider a number of key priority areas :

- The need for quality data

- Good regulation and standards which gain public trust

- Jobs and Skills

- International cooperation especially in R&D eg Horizon

- Investment incentives

- Infrastructure

TechUk reported earlier this year at London Tech Week that UK start-up investment saw the biggest annual opening on record in 2022, with $11.3B raised by UKstart-ups in Q1, compared to $7.9b in Q1 2021.The UK is home to 122 unicorns, behind only the USand China for the creation of billion dollar tech companies, and first in Europe..

This is undoubtedly positive, especially considering the wider economic challenges the UK and the world face. However, with the UK economy forecasted to face a recession and an economic slowdown forecasted for 2023-2026, we cannot be complacent,

Moreover as the Entrepreneurs Network point out in your recent paper making Britain the best place for AI Innovation, while the UK is a global leader in research, development and talent, the Tortoise Index ranks Government strategy - defined as financial and procedural investment into AI - only 13th internationally, which puts it behind Belgium.

First of all if we are to have an AI growth Strategy there is need for a quality data

We need independent measures of platform business, their economic activity, growth rates, national and regional figures that can reveal hotspots of growth as well as cold spots for future investment and development.It seems that organisations such as the ONS don’t gather relevant data. It is difficult to develop a growth strategy for AI when the baseline from which to compare the growth isn't available.

We also need data that cover different dimensions of growth –there need to be quality measures – quality of jobs, income, service, work/life balance etc.

Good regulation and standards

Then we have the importance of certainty for business of clear regulation.progress on AI governance and regulation is important as well to restore and retain Public Trust..

Regulation is not necessarily the enemy of innovation, it can in fact be the stimulus and be the key to gaining and retaining public trust around AI and its adoption

One of the main areas of focus of our original AI Select Committee was the need to develop an appropriate ethical framework for the development and application of AI and we were early advocates for international agreement on the principles to be adopted. It has become clear that voluntary ethical guidelines however much they are widely shared, are not enough to guarantee ethical AI and gain trust.

Some of the institutions envisaged as the core of AI development really are working well. The Turing for example is coordinating effectively such as through the new AI Standards Hub But CDEI has lost its way and not been given enough independence and the Office for AI has lost impetus. The Digital Catapult has considerable expertise and great potential but is underresourced.

A key development in the last two years has been the work done at international level in the Council of Europe, OECD, UNESCO and EU towards putting these principles into practice . The only international forum where the government seem to want to make a real contribution however is the global partnership on AI GPAI

If at minimum we could agree international standards for AI Risk Assessment and Audit that would represent realm progress and give our developers real certainty.

The UK’s National AI strategy accepts the fact that we need to prepare for AGI

On the other hand despite little appetite in the business or the research communities they have now introduced a new a really unhelpful Bill on major changes to the GDPR post Brexit and as a result we may have a less independent ICO which will put at risk the precious Data Adequacy ruling by the EU.

And above all despite their commitment to trustworthy AI, we still await the Government’s proposals on AI Governance in the forthcoming White Paper but there is a strong prediction that it will be mainly sectoral;/contextual and not in line with our EU partners or even extraordinarily the US.

At the very least we also need to be mindful that the extraterritoriality of the EU AI Act means a level of regulatory conformity will be required for the benefit of our developers and cross border business

Jobs and Skills

Then of course we have the potential impact of AI on jobs and employment . A report by Microsoft quoted by TEN found that the UK is facing an AI skills shortage: only 17% of UK employees are being re-skilled for AI

We need to ensure that people have the opportunity to reskill and retrain to be able to adapt to the evolving labour market caused by AI. Every child should leave school with a basic sense of how AI works.

But the pace, scale and ambition of government action does not match the challenge facing many people working in the UK. The Skills and post 16 Education Act with its introduction of a Lifelong Loan Entitlement is a step in the right direction.I welcome the renewed emphasis on Further Education and the new institutes of Technology.. but this isn’t ambitious enough.

The government refer to AI apprenticeships but Apprentice Levy reform is long overdue. The work of Local Digital Skills Partnerships and Digital Boot camps is welcome but they are greatly under-resourced and only a patchwork. Careers advice and Adult education need a total revamp

We also need to attract foreign talent. Immigration has a positive impact on innovation.The new Global Talent visa seeks to attract leaders or potential leaders in various fields including digital technology. This and changes the changes to the Innovator visa are welcome.

Broader digital literacy is crucial. We need to learn how to live and work alongside AI and a specific training scheme should be designed to support people to work alongside AI and automation, and to be able to maximise its potential

Given the current and imminently greater disruption in the job market we need to modernise employment rights to make them fit for the age of the AI driven ‘gig economy’, in particular by establishing a new ‘dependent contractor’ employment status in between employment and self-employment, with entitlements to basic rights such as minimum earnings levels, sick pay and holiday entitlement.

Alongside this we shared the priority of the AI Council Roadmap for more diversity and inclusion in the AI workforce and we still need to see more progress in this area.

R & D support including International cooperation eg Horizon

Any industrial policy for AI needs to discuss the R & D and innovation context in which it is designed to sit.

The UK has/had a long-term target for UK R&D to reach 2.4% of GDP by 2027. In 2020 we had the very well-intentioned R & D Roadmap. Since then we have had the UK Innovation Strategy with its Vision 2035, the AI Strategy, the Lifesciences Vision, the Fintech Strategic Review, all it seems informed by the Integrated Review’s determination that we will have secured our status as a science and tech superpower by 2030.

So there is no shortage of roadmaps, reviews and strategies which lay out government policy in this landscape!

Lord Hague wrote a wise piece in the Times a little time ago. he said

“But the officials working on so many new strategies should be running down the corridors by now and told to come back only when they have some detailed plans that go far beyond expressing our ambitions”

When we wrote our AI reports in 2018 and 2020 it was clear to us that the UK remained attractive to international research talent. I am still very enthusiastic about the future of UK research & development, innovation and their commercial translation in the UK and want them to thrive for all our benefit

University R& D remains important.There are strong concerns about the availability of research visas available for entrance to universities research programmes and the failure to agree and the lack of access to EU Horizon research Council funding could have a huge impact. Plan B by the sound of it won’t give us anything like the same benefits. A number of Russell group universities such as imperial UCL and my own Queen Mary are now with finance partners building spin out funds.

Additional funding could be provided to leading research universities to fund postgraduate scholarships in AI-related fields. .We should be seeking to make universities regional powerhouses tied in with the economic future of our city regions through university enterprise zones

We do nevertheless rank highly in the world of early-stage research and some late stage not least in AI, but it is in commercialisation- translational research and industrial R&D-where we continue to fall down.

The UK is a top nation in the global impact of its R&D, but not so effective at innovation, where it ranks 11th in the world in terms of knowledge diffusion and 27th for knowledge absorption, according to an October 2021 report by BEIS.

As Lord Willets is quoted as saying in a recent excellent HEPI paper (see how i quote tory peers!) “Catching the wave: harnessing regional research and development to level up ‘We all know the problem– we have great universities and win Nobel Prizes, but we don’t do so well at commercialisation’.

Our research sponsoring bodies could be more generous in their funding, with less micromanagement, less keen digging up projects by the roots to see if they are growing. The creation of ARIA was an admission of the bureaucratic nature the current UKRI research funding system

I welcome moves to extend R&D tax credits to investment in cloud computing infrastructure and data cost, but We need to bring in capital expenditure costs, such as those on plant and machinery for facilities engaging in R&D within scope as Tech UK have called for.I think we should now consider for AI investment something akin to the dedicated film tax credit for AI investment which has been so successful to date.

There needs to be more support for Catapults which have crucial roles as technology and innovation centre as the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee Report this year recommended

We could also emulate America’s seed fund- the SBIR and STTR programs which are at much great scale than our albeit successful UK Innovation and Science Seed Fund (UKI2S). And we need to expand the role of our low profile British Business bank

Infrastructure

There has been so much government bravado in this area but is clear that the much trumpeted £5 billion announced last year for Project Gigabit bringing gigabit coverage to the hardest to reach areas has not even been fully allocated and barely a penny has been spent.

But the Government is still not achieving its objectives.

The latest Ofcom figures show it seems that 90% of houses are covered by superfast broadband but the urban rural gap is still wide.

While some parts of the country are benefiting from high internet speeds, others have been left behind, The UK has nearly 5mn houses with more than three choices of ultrafast fibre optic broadband, while 10mn homes do not have a single option. According to the latest government data, in January 2022, 70 per cent of urban premises across the UK had access to gigabit-capable broadband, compared with 30 per cent of rural ones.

In fact urban areas now risk being overbuilt with fibre. In many towns and cities, at least three companies are digging to lay broadband fibre cables all targeting the same households, with some areas predicted to have six or seven such lines by the end of the decade.

So are we now into a wild west for the laying of fibre optic cable Is this going to be like the Energy market with great numbers of companies going bust.

So sadly even our infrastructure rollout is not very coherent!

.

Freedom of Expression Compatible with Child Protection says Lord C-J

The House of Lords recently debated the report of the Communivccations and digitl Select Committee Repotry entitled Free For All? Freedom of Expression in the Digital Age.

This is an edited version of what I said in the debate.

I congratulate the Select Committee on yet another excellent report relating to digital issues It really has stimulated some profound and thoughtful speeches from all around the House. This is an overdue debate.

As someone who sat on the Joint Committee on the draft Online Safety Bill, I very much see the committee’s recommendations in the frame of the discussions we had in our Joint Committee. It is no coincidence that many of the Select Committee’s recommendations are so closely aligned with those of the Joint Committee, because the Joint Committee took a great deal of inspiration from this very report—I shall mention some of that as we go along.

By way of preface, as both a liberal and a Liberal, I still take inspiration from JS Mill and his harm principle, set out in On Liberty in 1859. I believe that it is still valid and that it is a concept which helps us to understand and qualify freedom of speech and expression. Of course, we see Article 10 of the ECHR enshrining and giving the legal underpinning for freedom of expression, which is not unqualified, as I hope we all understand.

There are many common recommendations in both reports which relate, in the main, to the Online Safety Bill—we can talk about competition in a moment. One absolutely key point made during the debate was the need for much greater clarity on age assurance and age verification. It is the friend, not the enemy, of free speech.

The reports described the need for co-operation between regulators in order to protect users. On safety by design, both reports acknowledged that the online safety regime is not essentially about content moderation; the key is for platforms to consider the impact of platform design and their business models. Both reports emphasised the importance of platform transparency. Law enforcement was very heavily underlined as well. Both reports stressed the need for an independent complaints appeals system. Of course, we heard from all around the House today the importance of media literacy, digital literacy and digital resilience. Digital citizenship is a useful concept which encapsulates a great deal of what has been discussed today.

The bottom line of both committees was that the Secretary of State’s powers in the Bill are too broad, with too much intrusion by the Executive and Parliament into the work of the independent regulator and, of course, as I shall discuss in a minute, the “legal but harmful” aspects of the Bill. The Secretary of State’s powers to direct Ofcom on the detail of its work should be removed for all reasons except national security.

A crucial aspect addressed by both committees related to providing an alternative to the Secretary of State for future-proofing the legislation. The digital landscape is changing at a rapid pace—even in 2025 it may look entirely different. The recommendation—initially by the Communications and Digital Committee—for a Joint Committee to scrutinise the work of the digital regulators and statutory instruments on digital regulation, and generally to look at the digital landscape, were enthusiastically taken up by the Joint Committee.

The committee had a wider remit in many respects in terms of media plurality. I was interested to hear around the House support for this and a desire to see the DMU in place as soon as possible and for it to be given those ex-ante powers.

Crucially, both committees raised fundamental issues about the regulation of legal but harmful content, which has taken up some of the debate today, and the potential impact on freedom of expression. However, both committees agreed that the criminal law should be the starting point for regulation of potentially harmful online activity. Both agreed that sufficiently harmful content should be criminalised along the lines, for instance, suggested by the Law Commission for communication and hate crimes, especially given that there is now a requirement of intent to harm.

Under the new Bill, category 1 services have to consider harm to adults when applying the regime. Clause 54, which is essentially the successor to Clause 11 of the draft Bill, defines content that is harmful to adults as that

“of a kind which presents a material risk of significant harm to an appreciable number of adults in the United Kingdom.”

Crucially, Clause 54 leaves it to the Secretary of State to set in regulations what is actually considered priority content that is harmful to adults.

The Communications and Digital Committee thought that legal but harmful content should be addressed through regulation of platform design, digital citizenship and education. However, many organisations argue especially in the light of the Molly Russell inquest and the need to protect vulnerable adults, that we should retain Clause 54 but that the description of harms covered should be set out in the Bill.

Our Joint Committee said, and I still believe that this is the way forward:

“We recommend that it is replaced by a statutory requirement on providers to have in place proportionate systems and processes to identify and mitigate reasonably foreseeable risks of harm arising from regulated activities defined under the Bill”, but that

“These definitions should reference specific areas of law that are recognised in the offline world, or are specifically recognised as legitimate grounds for interference in freedom of expression.”

We set out a list which is a great deal more detailed than that provided on 7 July by the Secretary of State. I believe that this could form the basis of a new clause. As my noble friend Lord Allan said, this would mean that content moderation would not be at the sole discretion of the platforms. The noble Lord, Lord Vaizey, stressed that we need regulation.

We also diverged from the committee over the definition of journalistic content and over the recognised news publisher exemption, and so on, which I do not have time to go into but which will be relevant when the Bill comes to the House. But we are absolutely agreed that regulation of social media must respect the rights to privacy and freedom of expression of people who use it legally and responsibly. That does not mean a laissez-faire approach. Bullying and abuse prevent people expressing themselves freely and must be stamped out. But the Government’s proposals are still far too broad and vague about legal content that may be harmful to adults. We must get it right. I hope the Government will change their approach: we do not quite know. I have not trawled through every amendment that they are proposing in the Commons, but I very much hope that they will adopt this approach, which will get many more people behind the legal but harmful aspects.

That said, it is crucial that the Bill comes forward to this House. Lord Gilbert, pointed to the Molly Russell inquest and the evidence of Ian Russell, which was very moving about the damage being wrought by the operation of algorithms on social media pushing self-harm and suicide content. I echo what the noble Lord said: that the internet experience should be positive and enriching. I very much hope the Minister will come up with a timetable today for the introduction of the Online Safety Bill.

At last... compensation for Hep C blood victims

Finally after 5 decades Haemophiliac victims of the contaminted Hepatitisis C blood scandal are due to receive compensation as a result of the recommendation of the Langstaff Enquiry ...although not their familes.

Something that successive governments of all parties have failed to do.

It reminds me that TWENTY YEARS AGO when I was the Lib Dem Health Spokesperson in the Lords we were arging for an enquiry and compensation from the Blair Government. Only now 2 decades later has it become a reality.

This is what I said at the time in a debate in April 2001 initiated by the late Lord Alf Morris, that great campaigner for the disabled, asking the government : "What further help they are considering for people who were infected with hepatitis C by contaminated National Health Service blood products and the dependants of those who have since died in consequence of their infection."

My Lords, I believe that the House should heartily thank the noble Lord, Lord Morris, for raising this issue yet again. It is unfortunate that I should have to congratulate the noble Lord on his dogged persistence in raising this issue time and time again. I can remember at least two previous debates this time last year and another in 1998. I remember innumerable Starred Questions on the subject, and yet the noble Lord must reiterate the same issues and points time and time again in debate. It is extremely disappointing that tonight we hold yet another debate to point out the problems faced by the haemophilia community as a result of the infected blood products with which the noble Lord has so cogently dealt tonight.

Many of us are only too well acquainted with the consequences of infected blood products which have affected over 4,000 people with haemophilia. We know that as a consequence up to 80 per cent of those infected will develop chronic liver disease; 25 per cent risk developing cirrhosis of the liver; and that between one and five per cent risk developing liver cancer. Those are appalling consequences.

Those who have hepatitis C have difficulty in obtaining life assurance. We know that they have reduced incomes as a result of giving up work, wholly or partially, and that they incur costs due to special dietary regimes that they must follow. We also know that the education of many young people who have been infected by these blood products has been adversely affected. The noble Lord, Lord Morris, was very eloquent in describing the discrimination faced by some of them at work, in school and in society, and their fears for the future. He referred to the lack of counselling support and the general inadequacy of support services for members of the haemophilia community who have been infected in this way.

There are three major, yet reasonable, demands made by the haemophilia community in its campaign for just treatment by the Government. To date, the

Department of Health appears to have resisted stoically all three demands. First, there is the lack of availability on a general basis of recombinant genetically-engineered blood products. Currently, they are available for all adults in Scotland and Wales but not in England and Northern Ireland. Do we have to see the emergence of a black market or cross-border trade in these recombinant products? Should not the Government make a positive commitment to provide these recombinant factor products for all adults in the United Kingdom wherever they live? Quite apart from that, what are the Government doing to ensure that the serious shortage of these products is overcome? In many ways that is as serious as the lack of universal availability. Those who are entitled to them find it difficult to get hold of them in the first place.

The second reasonable demand of the campaign is for adequate compensation. The contrast with the HIV/AIDS situation could not be more stark. The noble Lord, Lord Morris, referred to the setting up of the Macfarlane Trust which was given £90 million as a result of his campaigning in 1989. The trust has provided compensation to people with haemophilia who contracted HIV through contaminated blood products. But there is no equivalent provision for those who have contracted hepatitis C. The Government, in complete contrast to their stance on AIDS/HIV, have continued to reiterate that compensation will not be forthcoming. The Minister of State for Health, Mr Denham, said some time ago that at the end of the day the Government had concluded that haemophiliacs infected with hepatitis C should not receive special payments. On 29th March of this year the noble Lord, Lord Hunt, in response to a Starred Question tabled by the noble Lord, Lord Morris, said:

"The position is clear and has been stated policy by successive governments. It is that, in general, compensation is paid only where legal liability can be established. Compensation is therefore paid when it can be shown that a duty of care is owed by the NHS body; that there has been negligence; that there has been harm; and that the harm was caused by the negligence".—[Oficial Report, 29/3/01; col. 410.]

The Minister said something very similar on 26th March. This means that the Government have refused to regard a hepatitis C infection as a special case despite the way in which they have treated AIDS/HIV sufferers who, after all, were adjudged to be a special circumstance. These are very similar situations.

In our previous debate on this, noble Lords referred to the similarity between the viral infections. They are transmitted to haemophiliacs in exactly the same manner; they lead to debilitating illness, often followed by a lingering, painful death. I could consider at length the similarities between the two viral infections and the side effects; for example, those affected falling into the poverty trap. We have raised those matters in debate before and the Government are wholly aware of the similarities between the two infections.

The essence of the debate, and the reason for the anger in the haemophilia community, is the disparity in the treatment of haemophiliacs infected with HIV

and those who, in a sense, are even more unfortunate and have contracted hepatitis C. We now have the contrast with those who have a legal remedy, which was available as demonstrated in the case to which the noble Lord, Lord Morris, referred, and are covered by the Consumer Protection Act 1987. This latter case was in response to an action brought by 114 people who were infected with hepatitis by contaminated blood. The only difference between the cases that we are discussing today and the circumstances of those 114 people is the timing. Is it not serendipity that the Consumer Protection Act 1987 covers those 114 people but not those with haemophilia who are the subject of today's debate?

It is extraordinary that the Government—I have already quoted the noble Lord, Lord Hunt—take the view that it all depends on the strict legal position. Quite frankly, the issue is still a moral one, as we have debated in the past. In fact, the moral pressure should be increased when one is faced with the comparison with both that case and the HIV/AIDS compensation scheme. People with haemophilia live constantly with risk. We now have the risk of transmission of CJD/BSE. What will be the Government's attitude to that? Will they learn the lessons of the past? I hope that the Minister will give us a clear answer in that respect.

I turn to the third key demand of the campaign by the haemophilia community. Without even having had an inquiry, the NHS is asserting that no legal responsibility to people with haemophilia exists. The Government's position—that they will not provide compensation where the NHS is not at fault—falls down because that is precisely what the previous administration did in the case of those infected with HIV. An inquiry into how those with hepatitis C were infected would perhaps establish very similar circumstances.

Other countries such as France and Canada have held official inquiries. Why cannot we do the same in this country? The Government's refusal to instigate a public inquiry surely fails the morality test. Surely the sequence of events which led up to what has been widely referred to as one of the greatest tragedies in the history of the NHS needs to be examined with the utmost scrutiny. Why do the Government still refuse to set up an inquiry? Is it because they believe that if the inquiry reported it would demonstrate that the Government—the department—were at fault?

Doctors predict that the number of hepatitis C cases among both haemophiliacs and the general population is set to rise considerably over the next decade. The Department of Health should stop ignoring the plight of this group. They should start to treat it fairly and accede to its reasonable demands. The Government's attitude to date has been disappointing to say the least. This debate is another opportunity for them to redeem themselves.

Creating the best framework for AI in the UK

This is a short piece I wrote earlier in the year for the Foundation of Science & Technology about the future of AI regulation in the UK which has now appeared in the FST Journal

Summary

- AI is becoming embedded in everything we do

- We should be clear about the purpose and implications of new technologies

- There is a general acceptance of the need for a risk-based ethics regulatory framework

- The Humanities will be as important as STEM in the development of AI

- Every child leaving school should have an understanding of the basics of AI.

A little over five years ago, the Lord's AI select committee began its first inquiry. The resulting report was titled: AI in the UK: ready, willing and able? About the same time, the independent review Growing the Artificial Intelligence Industry in the UK set a baseline from which to work.

There will always be something of a debate about the definition of artificial intelligence. It is clear though that the availability of quality data is at the heart of AI applications. In the overall AI policy ecosystem, some of the institutions were newly established by Government, some of them recommended by the Hall review. There is the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation, the AI Council and the Office for AI. Standards development has been led by the Alan Turing Institute, the Open Data Institute, the Ada Lovelace Institute, the British Standards Institution and the Oxford Internet Institute, to name just a few.

Regulators include the Information Commissioner’s Office, Ofcom, the Financial Conduct Authority and the Competition & Markets Authority, which have come together under a new digital regulators’ cooperation forum to pool expertise. The Court of Appeal has also been grappling with issues relating to IP created by AI. Now regulation is not necessarily the enemy of innovation. In fact, it can be a stimulus and is the key to gaining and retaining public trust around AI, so that we can realise the benefits and minimise the risks. Algorithms have got a bad name over the past few years.

I believe that AI will actually lead to greater productivity and more efficient use of resources generally. However, technology is not neutral. We should be clear about the purpose and implications of new technology when we adopt it. Inevitably, there are major societal issues about the potential benefit from new technologies. Will AI better connect and empower our citizens improve working life?

In the UK, there is general recognition of the need for an ethics-based regulatory framework: this is what the forthcoming AI Governance white paper is expected to contain. The National Strategy also highlights the importance of public trust and the need for trustworthy AI.

We should be clear about the purpose and implications of new technology when we adopt it. Will AI better connect and empower our citizens?

The legal situation

The Government has produced a set of transparency standards for AI in the public sector (and, notably, GCHQ has produced a set of AI ethics for its operations). On the other hand, it has also been consulting on major changes to the GDPR post-Brexit, in particular a proposal to get rid of Article 22, the so-called ‘right to explanation’ where there is automated decision making (if anything, we need to extend this to decisions where there is already a human involved). There are no proposals to clarify data protection for behavioural or so-called inferred data, which are the bedrock of current social media business models, and will be even more important in what has been described as the metaverse. There is also a suggestion that firms may no longer be required to have a Data Protection Officer or undertake data protection impact assessments.

We have in fact no settled regulation, or legal framework, for intrusive AI technologies such as live facial recognition. This continues to be deployed by the police, despite the best efforts of a number of campaigning organisations and even successive biometrics and surveillance camera commissioners who have argued for a full legal framework. There are no robust compliance or redress mechanisms for ensuring ethical, transparent, automated decision-making in our public sector either.

It is not yet even clear whether the Government is still wedded to sectoral (rather than horizontal) regulation. The case is now irrefutable for a risk-based form of horizontal regulation, which puts into practice common ethical values, such as the OECD principles.

There has been a great deal of work internationally by the Council of Europe, OECD, UNESCO, the global partnership on AI, and especially the EU. The UK, therefore, needs a considerable degree of convergence between ourselves, the EU and members of the Council of Europe, for the benefit of our developers and cross-border businesses, to allow them to trade freely. Above all, this means agreeing on common standards for risk and impact assessments alongside tools for audit and continuous monitoring for higher-risk applications. In that way it may be possible to draw the USA into the fold as well. That is not to mention the whole defence and lethal autonomous systems space: we still await the promised defence AI strategy.

We have no settled regulation, or legal framework, for intrusive AI technologies such as live facial recognition.

We have no settled regulation, or legal framework, for intrusive AI technologies such as live facial recognition.

AI skills

AI is becoming embedded in everything we do. A huge amount is happening on supporting AI specialist skills development and the Treasury is providing financial backing. But as the roadmap produced by the AI Council itself points out, the Government needs to take further steps to ensure that the general digital skills and digital literacy of the UK are brought up to speed.

I do not believe that the adoption of AI will necessarily make huge numbers of people redundant. But as the pandemic recedes, the nature of work will change, and there will be a need for different jobs and skills. This will be complemented by opportunities for AI, so the Government and industry must ensure that training and retraining opportunities take account of this. The Lords AI Select Committee also shared the priority of the AI Council roadmap for diversity and inclusion in the AI workforce and wanted to see much more progress on this.

But we need however, to ensure that people have the opportunity to retrain in order to be able to adapt to the evolving labour market caused by AI. The Skills and Post-16 Education Bill with the introduction of a lifelong loan entitlement is welcome but is not ambitious enough.

A recent estimate suggests that 90% of UK jobs within 20 years will require digital skills. That is not just about STEM skills such as maths and coding. Social and creative skills as well as critical thinking will be needed. The humanities will be as important as the sciences, and the top skills currently being sought by tech companies, as the University of Kingston's future league table has shown, include many creative skills: problem solving, communication, critical thinking, and so on. Careers advice and Adult Education likewise need a total rethink.

We need to learn how to live and work alongside AI. The AI Council roadmap recommends an online academy for understanding AI. Every child leaving school should have a basic sense of how AI works. Finally, given the disruption in the job market, we need to modernise employment rights to make them fit for the age of the AI- driven gig economy, in particular by establishing a new dependent contractor employment status, which fits between employment and self-employment.

Government must ensure the regulation of election dis-and misinformation

Earlier this year during the Elections Bill process we debated the regulation of digital campaigning and how we needed to add new provisions to allow the Elections Commission to control misinformation and disinformation

This is what I said

Digital campaigning is of growing importance. It accounted for 42.8% of reported spend on advertising in the UK at the 2017 general election. That figure rose in 2019; academic research has estimated that political parties’ spending on platforms is likely to have increased by over 50% in 2019 compared to 2017. As the Committee on Standards in Public Life said in its report in July last year, Regulating Election Finance:

“Research conducted by the Electoral Commission following the 2019 General Election revealed that concerns about transparency are having an impact on public trust and confidence in campaigns.”

In that light, the introduction of digital imprints for political electronic material is an overdue but welcome part of the Elections Bill.

The proposed regime as it stands covers all types of digital material and all types of appropriate promoter. However, a significant weakness of the Bill may exist in the detail of where an imprint must appear. In its current form, the Bill allows promoters of electronic material to avoid placing an imprint on the material itself if it is not reasonably practicable to do so. Instead, campaigners could include the imprint somewhere else that is directly accessible from the electronic material, such as a linked webpage or social media profile or bio. The evidence from Scotland’s recent parliamentary elections is that this will lead in practice to almost all imprints appearing on a promoter’s website or homepage or on their social media profile, rather than on the actual material itself. Perhaps that was encouraged by the rather permissive Electoral Commission guidance for those elections.

Can this really be classed as an imprint? For most observers of the material, there will be no discernible change from the situation that we have now—that is, they will not see the promoter’s details. The Electoral Commission also says that this approach could reduce transparency for voters if it is harder to find the imprint for some digital campaign material. It seems that

“if it is not reasonably practicable to comply”

will award promoters with too much leeway to hide an imprint. Replacing that with

“if it is not possible to comply”

would ensure that the majority of electronic material is within the scope of the Bill’s intentions. What happened to the original statement in the Cabinet Office summary of the final policy in its response to the consultation document Transparency in Digital Campaigning in June last year? That says:

“Under the new regime, all paid-for electronic material will require an imprint, regardless of who it is promoted by.”

There is no mention of exemptions.

The commission says it is important that the meanings of the terms in the Bill are clear and unambiguous, and that it needs to know what the Government’s intent is in this area. In what circumstances do the Government really believe it reasonable not to have an imprint but to have it on a website or on a social media profile? We need a clear statement from them.

As my noble friend Lord Wallace said, Amendments 194A and 196A really should be included in the “missed opportunity” box, given the massive threat of misinformation and disinformation during election campaigns, particularly by foreign actors, highlighted in a series of reports by the Electoral Commission, the Intelligence and Security Committee and the Committee on Standards in Public Life, as well as by the Joint Committee on the Draft Online Safety Bill, on which I sat. It is vital that we have much greater regulation over this and full transparency over what has been paid for and what content has been paid for. As the CSPL report last July said,

“digital communication allows for a more granular level of targeting and at a greater volume – meaning more messages are targeted, more precisely and more often.”

The report says:

“The evidence we have heard, combined with the conclusions reached by a range of expert reports on digital campaigning in recent years, has led us to conclude that urgent action is needed to require more information to be made available about how money is spent on digital campaigning.”

It continues in paragraph 6.26:

“We consider that social media companies that permit campaign adverts in the UK should be obliged to create advert libraries. As a minimum they should include adverts that fit the legal definition of election material in UK law.”

The report recommends that:

“The government should change the law to require parties and campaigners to provide the Electoral Commission with more detailed invoices from their digital suppliers … subdivide their spending returns to record what medium was used for each activity”

and

“legislate to require social media platforms that permit election adverts in the UK to create advert libraries that include specified information.”

All those recommendations are also contained in the Electoral Commission report, Digital Campaigning: Increasing Transparency for Voters from as long ago as June 2018, and reflect what the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation set out in its February 2020 report on online targeting in specifying what it considered should be included in any such advert library. The implementation of these recommendations, which are included in Amendment 196A, would serve to greatly increase the financial transparency of digital campaigning operations.

In their response to the CSPL report, the Government said:

“The Government is committed to increasing transparency in digital campaigning to empower voters to make decisions. As part of this, we take these recommendations on digital campaigning seriously. As with all of the recommendations made by the CSPL, the Government will look in detail at the recommendations and consider the implications and practicalities.”

The Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee report last December followed that up, saying at paragraph 216:

“The Government’s response to the CSPL report on electoral finance regulation provides no indication of which of its recommendations (not already included in the Bill) the Government is likely to adopt … prioritise for consultation or when or how the Government proposes to give legislative effect to recommendations that will not be included in the Bill. The Government should give clarity on its next steps in this regard.”

So the time has come for the Government to say what their intentions are. They have had over six months to do this, and I hope they have come to the conclusion that fully safeguards our democracy. I hope the Government will now see the merits and importance of those amendments.

The CSPL also recommended changes to electoral law regarding foreign actors. The CSPL says at paragraph 6.29 of its report:

“As we discuss in chapter 4, the rules on permissible donations were based on the principle that there should be no foreign interference in UK elections. However, the rules do not explicitly ban spending on campaign advertising by foreign individuals or organisations.”

It specifically refers to the Electoral Commission’s Digital Campaigning report, which said:

“A specific ban on any campaign spending from abroad would … strengthen the UK’s election and referendum rules.”

It quoted the DCMS committee’s February 2019 report, Disinformation and “Fake News”, which said that

“the UK is clearly vulnerable to covert digital influence campaigns”,

and the Intelligence and Security Committee report, which stated that if the commission

“is to tackle foreign interference, then it must be given the necessary legislative powers.”

These are powerful testimonies and recommendations from some very well respected committees. As a result, the CSPL recommended:

“In line with the principle of no foreign interference in UK elections, the government should legislate to ban foreign organisations or individuals from buying campaign advertising in the UK.”

This is very similar to a recommendation in the Electoral Commission’s Digital Campaigning: Increasing Transparency for Voters report of 2018, which I referred to earlier. In response, the Government said: “We are extending this”—the prohibition of foreign money—

“even further as part of the Elections Bill, to cover all third-party spending above £700 during a regulated period.”

However, the current proposals in the Bill have loopholes that foreign organisations can readily use, for instance through setting up multiple channels. A foreign actor could set up dozens of entities and spend £699 on each one—something very easy for online expenditure.

Amendment 194B would ensure that foreign entities were completely banned from participating at all and would make absolutely certain that the Government’s intentions were fulfilled. Again, I hope that the Minister will readily accept this amendment as strengthening the Bill against foreign interference.

Tackling societal harms caused by misinformation and disinformation is not straightforward, as our Joint Committee on the Online Safety Bill found. However, consistent with the report of the Lords Select Committee on Democracy and Digital Technologies, Digital Technology and the Resurrection of Trust, chaired by the much-missed Lord Puttnam, we said:

“Disinformation and Misinformation surrounding elections are a risk to democracy. Disinformation which aims to disrupt elections must be addressed by legislation. If the Government decides that the Online Safety Bill is not the appropriate place to do so, then it should use the Elections Bill which is currently making its way through Parliament.”

There is, of course, always a tension with freedom of expression, and as we emphasised in our Joint Committee, so we must prioritise tackling specific harmful activity over restricting content. Apart from the digital imprint provisions, however, the Bill fails to take any account of mounting evidence and concerns about the impact on our democracy of misinformation and disinformation. The long delayed report of the Intelligence and Security Committee on Russian interference of July 2020 was highly relevant in this context, stating:

“The UK is clearly a target for Russia’s disinformation campaigns and political influence operations and must therefore equip itself to counter such efforts.”

Protecting our democratic discourse and processes from hostile foreign interference is a central responsibility of the Government. The committee went on, very topically, to say:

“The links of the Russian elite to the UK—especially where this involves business and investment—provide access to UK companies and political figures, and thereby a means for broad Russian influence in the UK.”

It continued:

“We note—and, again, agree with the DCMS Select Committee—that ‘the UK is clearly vulnerable to covert digital influence campaigns.’”

The online harms White Paper published in April 2019 recognised the dangers that digital technology could pose to democracy and proposed measures to tackle them. Given the extensive regulatory framework being put in place for individual online harms in the Online Safety Bill, newly published last week, why are the Government reluctant to reaffirm the White Paper approach to elections and include it in this Bill? The Government responded to our Joint Committee report on this issue last week by saying that they agreed that misinformation and disinformation surrounding elections are a risk to democracy. However, they went on to say:

“The Government has robust systems in place that bring together governmental, civil society and private sector organisations to monitor and respond to interference in whatever form it takes to ensure that our democracy stays open, vibrant and transparent”

—fine words. They cite the Defending Democracy programme, saying:

“Ahead of major democratic events, the Defending Democracy programme stands up the Election Cell. This is a strategic coordination and risk reporting structure that works with relevant organisations to identify and respond to emerging issues”.

So far, so vague. They continue:

“The Counter Disinformation Unit based in DCMS is an integral part of this structure and undertakes work to understand the extent, scope and the reach of misinformation and disinformation.”

The Government, however, seem remarkably reluctant to tell us through parliamentary Questions or FoI requests what this Counter Disinformation Unit within the DCMS is. What does it actually do? Does it have a role during elections? Given that government response, it seems clear that the net result is that the Elections Bill has, and will have, no provisions relating to misinformation and disinformation.

Amendment 194B is a start and is designed to prevent one strand of disinformation, akin to the 640,000 Facebook posts that led to the Capitol riots of 6 January last year, which not only has immediate impact but erodes trust in future elections. The Government should pick this amendment up with enthusiasm but then introduce something much more comprehensive that meets the concerns of the ISC’s Russia report and tackles online misinformation and disinformation in election campaigns.

I would of course be very happy to discuss all these amendments and all the relevant issues with Ministers between Committee and Report stages.

Lord C-J introduces new Public Authority Algorithm Bill

I recently introduced a private members bill in the House of Lords designed to ensure that decisions made by public authorities-local and national -are fully transparent and propoerly assessed for the the impact they have on the rights of the individual citizen .

It mandates the government to draw up a framework for an impact assessment which follows a set of principles laid out in the Bill so that (a) decisions made in and by a public authority are responsible and comply with procedural fairness and due process requirements, and its duties under the Equality Act, (b) impacts of algorithms on administrative decisions are assessed and negative outcomes are minimized, and (c) data and information on the use of automated decision systems in public authorities are made available to the public. It will apply in general to to any automated decision system developed or procured by a public authority other than the security services

Lord C-J calls for review of Policy Lethal Autonomous Weapons

The Debate on limitation of Lethal Autonomous weapons has hotted up, especially in the the light of the Government's new Defence AI sttategy.

This is what I said prior to the report being published last when the Armed Forces Bill went thnrough the House of Lords

We eagerly await the defence AI strategy coming down the track but, as the noble Lord said, the very real fear is that autonomous weapons will undermine the international laws of war, and the noble and gallant Lord made clear the dangers of that. In consequence, a great number of questions arise about liability and accountability, particularly in criminal law. Such questions are important enough in civil society, and we have an AI governance White Paper coming down the track, but in military operations it will be crucial that they are answered.

From the recent exchange that the Minister had with the House on 1 November during an Oral Question that I asked about the Government’s position on the control of lethal autonomous weapons, I believe that the amendment is required more than ever. The Minister, having said:

“The UK and our partners are unconvinced by the calls for a further binding instrument”

to limit lethal autonomous weapons, said further:

“At this time, the UK believes that it is actually more important to understand the characteristics of systems with autonomy that would or would not enable them to be used in compliance with”

international human rights law,

“using this to set our potential norms of use and positive obligations.”

That seems to me to be a direct invitation to pass this amendment. Any review of this kind should be conducted in the light of day, as we suggest in the amendment, in a fully accountable manner.

However, later in the same short debate, as noted by the noble Lord, Lord Browne, the Minister reassured us, as my noble friend Lady Smith of Newnham noted in Committee, that:

“UK Armed Forces do not use systems that employ lethal force without context-appropriate human involvement.”

Later, the Minister said:

“It is not possible to transfer accountability to a machine. Human responsibility for the use of a system to achieve an effect cannot be removed, irrespective of the level of autonomy in that system or the use of enabling technologies such as AI.”—[Official Report, 1/11/21; col. 994-95.]

The question is there. Does that mean that there will always be a human in the loop and there will never be a fully autonomous weapon deployed? If the legal duties are to remain the same for our Armed Forces, these weapons must surely at all times remain under human control and there will never be autonomous deployment.

However, that has recently directly been contradicted. The noble Lord, Lord Browne has described the rather chilling Times podcast interview with General Sir Richard Barrons, the former Commander Joint Forces Command. He contrasted the military role of what he called “soft-body humans”—I must admit, a phrase I had not encountered before—with that of autonomous weapons, and confirmed that weapons can now apply lethal force without any human intervention. He said that we cannot afford not to invest in these weapons. New technologies are changing how military operations are conducted. As we know, autonomous drone warfare is already a fact of life: Turkish autonomous drones have been deployed in Libya. Why are we not facing up to that in this Bill?

I sometimes get the feeling that the Minister believes that, if only we read our briefs from the MoD diligently enough and listened hard enough, we would accept what she is telling us about the Government’s position on lethal autonomous weapons. But there are fundamental questions at stake here which remain as yet unanswered. A review of the kind suggested in this amendment would be instrumental in answering them.

Coordination of Digital Regulation Crucial

The House of Lords recently debated the report of its Select Committee on Communications and Digital entitled "Digital regulation: joined-up and accountable"

This is what I said about the shape digital regulation should take and how it could best be coordinated

In their digital regulation plan, first published last July and updated last month, the Government acknowledged that

“Digital technologies … demand a distinct regulatory approach … because they have distinctive features which make digital businesses and applications unique and innovative, but may also challenge how we address risks to consumers and wider society.”

I entirely agree, but I also agree with the noble Baroness, Lady Stowell, the noble Lord, Lord Vaizey, and the noble Earl, Lord Erroll, that we need to do this

without the kind of delays in introducing regulation that we are already experiencing.

The plan for digital regulation committed to ensuring a forward-looking and coherent regulatory approach for digital technologies. The stress throughout the plan and the digital strategy is on a light-touch and pro-innovation regulatory regime, in the belief that this will stimulate innovation. The key principles stated are “Actively promote innovation”, achieve “forward-looking and coherent outcomes” and

“Exploit opportunities and address challenges in the international arena”.

This is all very laudable and reinforced by much of what the Select Committee said in its previous report, as mentioned by the noble Baroness. But one of the key reasons why the design of digital governance and regulation is important is to ensure that public trust is developed and retained in an area where there is often confusion and misunderstanding.

With the Online Safety Bill arriving in this House soon, we know only too well that the power of social media algorithms needs taming. Retention of public trust has not been helped by confusion over the use of algorithms to take over exam assessment during the pandemic and poor communication about the use of data on things like the Covid tracing app, the GP data opt-out and initiatives such as the Government’s single-ID identifier “One Login” project, which, together with the growth of automated decision-making, live facial recognition and use of biometric data, is a real cause for concern for many of us.

The fragility of trust in government use and sharing of personal data was demonstrated when Professor Ben Goldacre recently gave evidence to the Science and Technology Committee, explaining that, despite being the Government’s lead adviser on the use of health data, he had opted out of giving permission for his GP health data to be shared.

As an optimist, I believe that new technology can potentially lead to greater productivity and more efficient use of resources. But, as the title of Stephanie Hare’s new book puts it, Technology Is Not Neutral. We should be clear about the purpose and implications of new technology when we adopt it, which means regulation which has the public’s trust. For example, freedom from bias is essential in AI systems and in large part depends on the databases we use to train AI. The UK’s national AI strategy of last September does talk about public trust and the need for trustworthy AI, but this needs to be reflected in our regulatory landscape and how we regulate. In the face of the need to retain public trust, we need to be clear, above all, that regulation is not necessarily the enemy of innovation; in fact, it can be the stimulus and key to gaining and retaining public trust around digital technology and its adoption.

We may not need to go full fig as with the EU artificial intelligence Act, but the fact is that AI is a very different animal from previous technology. For instance, not everything is covered by existing equalities or data protection legislation, particularly in terms of accountability, transparency and explainability. A considerable degree of horizontality across government, business and society is needed to embed the OECD principles.

As the UK digital strategy published this month makes clear, there is a great deal of future regulation in the legislative pipeline, although, as the noble Baroness mentioned, we are lagging behind the EU. As a number of noble Lords mentioned, we are expecting a draft digital competition Bill in the autumn which will usher in the DMU in statutory form and a new pro-competition regime for digital markets. Just this week, we saw the publication of the new Data Protection and Digital Information Bill, with new powers for the ICO. We have also seen the publication of the national AI strategy, AI action plan and AI policy statement.

In the context of increased digital regulation and the need for co-ordination across regulators, the Select Committee welcomed the formation of the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum by the ICO, CMA, Ofcom and FCA, and so do I, alongside the work plan which the noble Baroness, Lady Stowell, mentioned. I believe that this will make a considerable contribution to public trust in regulation. It has already made great strides in building a centre of excellence in AI and algorithm audit.

UK Digital Strategy elaborates on the creation of the DRCF:

“We are also taking steps to make sure the regulatory landscape is fully coherent, well-coordinated and that our regulators have the capabilities they need … Through the DRCF’s joint programme of work, it has a unique role to play in developing our pro-innovation approach to regulation.”

Like the Select Committee in one of its key recommendations, I believe we can go further in ensuring a co-ordinated approach to digital regulation, horizon scanning—which has been mentioned by all noble Lords—and adapting to future regulatory needs and oversight of fitness for purpose, particularly the desirability of a statutory duty to co-operate and consult with one another. It is a proposal which the Joint Committee on the Draft Online Safety Bill, of which I was a member, took up with enthusiasm. We also agreed with the Select Committee that it should be put on a statutory footing, with the power to resolve conflicts by directing its members. I was extremely interested to hear from noble Lords, particularly the noble Lord, Lord Vaizey, and the noble Earl, Lord Erroll, about the circumstances in which those conflicts need to be resolved. It is notable that the Government think that that is a bridge too far.

This very week, the Alan Turing Institute published a very interesting report entitled Common Regulatory Capacity for AI. As it says, the use of artificial intelligence is increasing across all sectors of the economy, which raises important and pressing questions for regulators. Its very timely report presents the results of research into how regulators can meet the challenge of regulating activities transformed by AI and maximise the potential of AI for regulatory innovation.

It takes the arguments of the Select Committee a bit further and goes into some detail on the capabilities required for the regulation of AI. Regulators need to be able to ensure that regulatory regimes are fit for AI and that they are able to address AI-related risks and maintain an environment that encourages innovation. It stresses the need for certainty about regulatory expectations, public trust in AI technologies and the avoidance of undue regulatory obstacles.

Regulators also need to understand how to use AI for regulation. The institute also believes that there is an urgent need for an increased and sustainable form of co-ordination on AI-related questions across the regulatory landscape. It highlights the need for access to new sources of shared AI expertise, such as the proposed AI and regulation common capacity hub, which

“would have its home at a politically independent institution, established as a centre of excellence in AI, drawing on multidisciplinary knowledge and expertise from across the national and international research community.”

It sets out a number of different roles for the newly created hub.

To my mind, these recommendations emphasise the need for the DRCF to take statutory form in the way suggested by the Select Committee. But, like the Select Committee, I believe that it is important that other regulators can come on board the DRCF. Some of them are statutory, such as the Gambling Commission, the Electoral Commission and the IPO, and I think it would be extremely valuable to have them on board. However, some of them are non-statutory, such the BBFC and the ASA. They could have a place at the table and join in benefiting from the digital centre of excellence being created.

Our Joint Committee also thoroughly agreed with the Communications and Digital Committee that a new Joint Committee on digital regulation is needed in the context of the Online Safety Bill. Indeed the Secretary of State herself has expressed support. As the Select Committee recommended, this could cover the broader digital landscape to partly oversee the work of the DRCF and also importantly address other objectives such as scrutiny of the Secretary of State, looking across the digital regulation landscape and horizon scanning—looking at evolving challenges, which was considered very important by our Joint Committee and the Select Committee.

The Government are engaged in a great deal of activity. The question, as ever, is whether the objectives, such as achieving trustworthy AI, digital upskilling and powers for regulators, are going to be achieved through the actions being taken so far. I believe that the recommendations of the Select Committee set out in this report would make a major contribution to ensuring effective and trustworthy regulation and should be supported.

Broadband and 5G rollout strategy needs review

During the passage of the Product and Security Bill it has become clear that the Government's rollout strategy keeps being changed and is unlikely to achieve its objectives, especially in rural areas. This is what I said when supporting a review.

We all seem to be trapped in a time loop on telecoms, with continual consultations and changes to the ECC and continual retreat by the Government on their 1 gigabit per second broadband rollout pledge. In the Explanatory Notes, we were at 85% by 2025; this now seems to have shifted to 2026. There has been much government bravado in this area, but it is clear that the much-trumpeted £5 billion announced last year for project gigabit, to bring gigabit coverage to the hardest-to-reach areas, has not yet been fully allocated and that barely a penny has been spent.

Then, we have all the access and evaluation amendments to the Electronic Communications Code and the Digital Economy Act 2017. Changes to the ECC were meant to do the trick; then, the Electronic Communications and Wireless Telegraphy (Amendment) (European Electronic Communications Code and EU Exit) Regulations were heralded as enabling a stronger emphasis on incentivising investment in very high capacity networks, promoting the efficient use of spectrum, ensuring effective consumer protection and engagement and supporting the Government’s digital ambitions and plans to deliver nationwide gigabit-capable connectivity.

Then we had the Future Telecoms Infrastructure Review. We had the Telecommunications Infrastructure (Leasehold Property) Act—engraved on all our hearts, I am sure. We argued about the definition of tenants, rights of requiring installation and rights of entry, and had some success. Sadly, we were not able to insert a clause that would have required a review of the Government’s progress on rollout. Now we know why. Even while that Bill was going through in 2021, we had Access to Land: Consultation on Changes to the Electronic Communications Code. We knew then, from the representations made, that the operators were calling for other changes not included in the Telecommunications Infrastructure (Leasehold Property) Act or the consultation. From the schedule the Minister has sent us, we know that he has been an extremely busy bee with yet further discussions and consultations.

I will quote from a couple of recent Financial Times pieces demonstrating that, with all these changes, the Government are still not achieving their objectives. The first is headed: “Broadband market inequalities test Westminster’s hopes of levelling up: Disparity in access to fast internet sets back rural and poorer areas, data analysis shows”. It starts:

“The UK has nearly 5mn houses with more than three choices of ultrafast fibre-optic broadband, while 10mn homes do not have a single option, according to analysis that points to the inequality in internet infrastructure across Britain.

While some parts of the country are benefiting from high internet speeds, others have been left behind, according to research conducted by data group Point Topic with the Financial Times, leading to disparities in people’s ability to work, communicate and play.”

A more recent FT piece from the same correspondent, Anna Gross, is headed: “UK ‘altnets’ risk digging themselves into a hole: Overbuilding poses threat to business model of fibre broadband groups challenging the big incumbents”. It starts:

“Underneath the UK’s streets, a billion-pound race is taking place. In many towns and cities, at least three companies are digging to lay broadband fibre cables all targeting the same households, with some areas predicted to have six or seven such lines by the end of the decade.

But only some of them will cross the finishing line … When the dust settles, will there be just two network operators—with Openreach and Virgin Media O2 dominating the landscape—or is there space for a sparky challenger with significant market share stolen from the incumbents?”