Opening the new AI and Innovation Centre at Buckingham University

Great to open the new centre with the assistance of Spot the Boston Dynamics dog!

Here is what I said

I am thrilled to assist with the opening of this trailblazing Artificial Intelligence and Innovation Centre. It’s fantastic to see this collaboration between the Buckinghamshire Local Enterprise Partnership through its Growth Fund and the University which will result in pioneering AI, cyber and robotics, help to produce the next generation of leaders in computing and the development of ground-breaking technology in Buckinghamshire, working especially with the Silverstone Park and Wescott Enterprise Zone.

Many of us -including Silicon Valley Billionaires it seems-read science fiction for pleasure, inspiration, and as a way of coming to terms with potential future technology . But little did I think when young and I read Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy or watched RUR the 1920 science-fiction play by Karel Capek, that invented the word “robot”, that I would many years later be helping open an AI and Innovation Centre at a major university!

It is significant that the Centre is not just located within the School of Computing (home to Spot the Boston Dynamics Dog and Birdly, the VR bird experience) but it is part of the University’s Faculty of Computing, Law and Psychology and I was particularly delighted to hear of the existing cross disciplinary faculty work on Games and VR, Fintech law, and human robotics interaction, cyber bullying and cyber psychology.

As a lawyer, my own involvement I think demonstrates the cross disciplinary nature nowadays of so much to do with AI and machine learning. The Lords Select Committee on AI which I chaired a few years ago emphasized this in calling for an ethical framework for the development and application of AI. Working that through to regulation, nationally and internationally will involve cross disciplinary skills and knowledge. AI developers need to have a broad understanding of the societal and ethical context in which they operate as well as technical skills.

Asimov’s 3 laws of robotics were a deliberate response to the kind of situation depicted in R.U.R, so the need for ethics and regulation was conceived from the dawn of AI and robotics. You may also remember of course that the centrepiece of the Foundation Books, Hari Seldon (no relation) creates the Foundations—two groups of sociologists, scientists and engineers at opposite ends of the galaxy—to preserve the spirit of science and civilization, and thus become the cornerstones of the new galactic empire. Early cross disciplinarity!

On an international if not galactic stage however, the University can take great pride in hosting the Institute for Ethical AI in Education which I had the privilege of chairing and which developed a highly influential Ethical Framework for AI in Education which will I hope stand the test of time.

This brings me on to another aspect of cross disciplinarity- creativity. Creative skills in how to use AI and other new technology will be vital. Take for example the play “AI” recently featured in Rory Cellan-Jones’ BBC Technology blog. This is a new a play developed alongside AI using the deep-learning system GPT-3 to generate human-like dialogue and script, and as they describe it “As artists and intelligent systems collide, AI asks us to consider the algorithms at work in the world around us, and what technology can teach us about ourselves”. Reassuringly the director and Rory both concluded that human input for a fully satisfying dramatic product was still essential!

Another aspect which cross disciplinary work brings is to ensure wider perspectives to the development of AI and other new technology. Diversity in those who oversee the development and application of AI is crucial, as we highlighted in our original AI Select Committee Report. Failing this as we said we will fail to spot bias in the data sets and repeat the prejudices of the past.

Finally, I wanted to highlight the leadership that the University and Buckinghamshire LEP are showing in this fied. Our AI Select Committee were confident that the UK could and would punch well above its weight in the development of AI and play an important international leadership role in both technological and ethical aspects. I congratulate you both for your vision in setting up the Centre which looks set fair to make a huge contribution to the UK’s leadership role.

Lord C-J : More Action on Algorithmic Decision Making Needed from Government to Uphold Nolan Standards

The Lords recently held a fascinating debate on Standards in Public Life. Here is what I said about the standards we need to apply to algorithmic decision making in Government.

https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2021-09-09/debates/4529BCC1-117D-4E8A-9DD8-A07CA472CD65/StandardsInPublicLife#contribution-AFAE87BA-AE61-4C0B-A79D-64627483A04F

My Lords, it is a huge pleasure to follow the noble Lord, Lord Puttnam. I commend his Digital Technology and the Resurrection of Trust report to all noble Lords who have not had the opportunity to read it. I thank the noble Lord, Lord Blunkett, for initiating this debate.

Like the noble Lord, Lord Puttnam, I will refer to a Select Committee report, going slightly off track in terms of today’s debate: last February’s Artificial Intelligence and Public Standards report by the Committee on Standards in Public Life, under the chairmanship of the noble Lord, Lord Evans of Weardale. This made a number of recommendations to strengthen the UK’s “ethical framework” around the deployment of AI in the public sector. Its clear message to the Government was that

“the UK’s regulatory and governance framework for AI in the public sector remains a work in progress and deficiencies are notable … on the issues of transparency and data bias in particular, there is an urgent need for … guidance and … regulation … Upholding public standards will also require action from public bodies using AI to deliver frontline services.”

It said that these were needed to

“implement clear, risk-based governance for their use of AI.”

It recommended that a mandatory public AI “impact assessment” be established

“to evaluate the potential effects of AI on public standards”

right at the project-design stage

The Government’s response, over a year later—in May this year—demonstrated some progress. They agreed that

“the number and variety of principles on AI may lead to confusion when AI solutions are implemented in the public sector”.

They said that they had published an “online resource”—the “data ethics and AI guidance landscape”—with a list of “data ethics-related resources” for use by public servants. They said that they had signed up to the OECD principles on AI and were committed to implementing these through their involvement as a

“founding member of the Global Partnership on AI”.

There is now an AI procurement guide for public bodies. The Government stated that

“the Equality and Human Rights Commission … will be developing guidance for public authorities, on how to ensure any artificial intelligence work complies with the public sector equality duty”.

In the wake of controversy over the use of algorithms in education, housing and immigration, we have now seen the publication of the Government’s new “Ethics, Transparency and Accountability Framework for Automated Decision-Making” for use in the public sector. In the meantime, Big Brother Watch’s Poverty Panopticon report has shown the widespread issues in algorithmic decision-making increasingly arising at local-government level. As decisions by, or with the aid of, algorithms become increasingly prevalent in central and local government, the issues raised by the CSPL report and the Government’s response are rapidly becoming a mainstream aspect of adherence to the Nolan principles.

Recently, the Ada Lovelace Institute, the AI Now Institute and Open Government Partnership have published their comprehensive report, Algorithmic Accountability for the Public Sector: Learning from the First Wave of Policy Implementation, which gives a yardstick by which to measure the Government’s progress. The position regarding the deployment of specific AI systems by government is still extremely unsatisfactory. The key areas where the Government are falling down are not the adoption and promulgation of principles and guidelines but the lack of risk-based impact assessment to ensure that appropriate safeguards and accountability mechanisms are designed so that the need for prohibitions and moratoria for the use of particular types of high-risk algorithmic systems can be recognised and assessed before implementation. I note the lack of compliance mechanisms, such as regular technical, regulatory audit, regulatory inspection and independent oversight mechanisms via the CDDO and/or the Cabinet Office, to ensure that the principles are adhered to. I also note the lack of transparency mechanisms, such as a public register of algorithms in operation, and the lack of systems for individual redress in the case of a biased or erroneous decision.

I recognise that the Government are on a journey here, but it is vital that the Nolan principles are upheld in the use of AI and algorithms by the public sector to make decisions. Where have the Government got to so far, and what is the current destination of their policy in this respect?

Lord Clement Jones calls for immediate moratorium on live facial recognition

![]()

POSTED ON BY GEORGIA MEYER

The rise of facial recognition technology has been described as “Orwellian” by Met Police Chief Cressida Dick.

Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/face-detection-scan-scanning-4791810/

Artificial intelligence technologies that are candidates for potential regulation were outlined in a speech to the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies’ annual conference.

A member of the House of Lords has called for an immediate halt to police use of live facial-recognition technology, during a speech to legal academics.

Liberal Democrat peer Lord Clement-Jones outlined his opposition to a range of AI technologies during his speech at the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies’ annual conference.

The peer, who is the co-chair of the parliamentary group on Artificial Intelligence, has previously proposed a private member’s bill in Parliament which seeks to ban the use of facial recognition in public places. The bill, which was tabled in February, is currently waiting for its second reading.

During his speech, Lord Clement-Jones outlined the wide variety of uses of AI in public life, many of which are positive, but highlighted certain areas that he believes should be “early candidates for regulation”.

These include the use of algorithmic decision-making in policing, the criminal justice system, recruitment processes, financial credit scoring and insurance premium setting. The peer sees the technologies as lacking transparency and accountability.

Lord Clement-Jones told the conference that current EU legislation is overly data-centric and fails to take account of the nuanced ways that algorithmic decision-making is being applied to many areas of our lives. The development of a ‘risk-mechanism’ in the law, to assess ethical dilemmas on a case by case basis, is critical, he said.

His remarks come a week after the UK Minister for Data, John Whittingdale, gave an upbeat speech about “unlocking the power of data and artificial intelligence to catalyse economic growth” in a post-Brexit UK, during his speech at the Open Data Institute.

Catalizing Cooperation:Working Together Accross AI Governance Initiatives

Here is the text and video of what I said at this stimulating and useful event hosted by the International Congress for the Goverance of AI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z_uji0LolLA

It is now my pleasure to introduce Lord Clement-Jones, also in a video presentation. He is the former chair of the House of Lords Select Committee on AI. He is the co-chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on AI, and he is a founding member of the OECD Parliamentary Group on AI and a member of the Council of Europe's ad hoc Committee on AI (CAHAI).

LORD TIM CLEMENT-JONES: Hello. It is great to be with you.

Today I am going to try to answer questions such as: What kind of international AI governance is needed? Can we build on existing mechanisms? Or does some new body need to be created?

As the House of Lords in our follow-up report, "AI in the UK: No Room for Complacency," last December strongly emphasized, it has never been clearer, particularly after this year of COVID-19 and our ever-greater reliance on digital technology, that we need to retain public trust in the adoption of AI, particularly in its more intrusive forms, and that this is a shared issue internationally. To do that, we need, whilst realizing the opportunities, to mitigate the risks involved in the application of AI, and this brings with it the need for clear standards of accountability.

The year 2019 was the year of the formulation of high-level ethical principles in the field of AI by the OECD, the European Union, and the G20. These are very comprehensive and provide the basis for a common set of international standards. For instance, they all include the need for explainability of decisions and an ability to challenge them, a process made more complex when decisions are made in the so-called "black box" of neural networks.

But it has become clear that voluntary ethical guidelines, however much they are widely shared, are not enough to guarantee ethical AI, and there comes a point where the risks attendant on noncompliance with ethical principles is so high that policymakers need to accept that certain forms of AI development and adoption require enhanced governance and/or regulation.

The key factor in 2020 has been the work done at international level in the Council of Europe, OECD, and the European Union towards putting these principles into practice in an approach to regulation which differentiates between different levels of risk and takes this into account when regulatory measures are formulated.

Last spring the European Commission published its white paper on the proposed regulation of AI by a principle-based legal framework targeting high-risk AI systems. As the white paper says, a risk-based approach is important to help ensure that the regulatory intervention is proportionate. However, it requires clear criteria to differentiate between the different AI applications, in particular in relation to the question or not of whether they are high-risk. The determination of what is a high-risk AI application should be clear, easily understandable, and applicable for all parties concerned.

In the autumn the European Parliament adopted its framework for ethical AI to be applicable to AI, robotics, and related technologies developed, deployed, and/or used within the European Union. Like the Commission's white paper, this proposal also targets high-risk AI. As well as the social and environmental aspects notable in this proposed ethical framework is the emphasis on human oversight required to achieve certification.

Looking through the lens of human rights, including democracy and the rule of law, the CAHAI last December drew up a feasibility study for regulation of AI, which likewise advocates a risk-based approach to regulation. It considers the feasibility of a legal framework for AI and how that might best be achieved. As the study says, these risks, however, depend on the application, context, technology, and stakeholders involved. To counter any stifling of socially beneficial AI innovation and to ensure that the benefits of this technology can be reaped fully while adequately tackling its risks, the CAHAI recommends that a future Council of Europe legal framework on AI should pursue a risk-based approach targeting the specific application context, and work is now ongoing to draft binding and non-binding instruments to take the study forward.

If, however, we aspire to a risk-based regulatory and governance approach, we need to be able to calibrate the risks, which will determine what level of governance we need to go to. But, as has been well illustrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, the language of risk is fraught with misunderstanding. When it comes to AI technologies we need to assess the risks by reference to the nature of AI applications and the context of their use. The potential impact and probability of harm, the importance and sensitivity of use of data, the application within a particular sector, the affected stakeholders, the risks of non-compliance, and whether a human in the loop mitigates risk to any degree.

In this respect, the detailed and authoritative classification work carried out by another international initiative, the OECD Network of Experts on AI working group, so-called "ONE AI," on the classification of AI systems comes at a crucial and timely point. This gives policymakers a simple lens through which to view the deployment of any particular AI system. Its classification uses four dimensions: context, i.e., sector, stakeholder, purpose, etc.; data and input; AI model, i.e., neural or linear, supervised or unsupervised; and tasks and output, i.e., what does the AI do? It ties in well with the Council of Europe feasibility work.

When it comes to AI technologies we need to assess the risks by reference to the nature of the AI applications and their use, and this kind of calibration, a clear governance hierarchy, can be followed depending on the level of risk assessed. Where the risk is relatively low, a flexible approach such as a voluntary ethical code without a hard compliance mechanism, can be envisaged, such as those enshrined in the international ethical codes mentioned earlier.

Where the risk is a step higher, enhanced corporate governance using business guidelines and standards with clear disclosure and compliance mechanisms needs to be instituted. Already at international level we have guidelines on government best practice, such as the AI procurement guidelines developed by the World Economic Forum, and these have been adopted by the UK government. Finally we may need to introduce comprehensive regulation, such as that which is being adopted for autonomous vehicles, which is enforceable by law.

Given the way the work of all of these organizations is converging, the key question of course is whether on the basis of this kind of commonly held ethical evaluation and risk classification and assessment there are early candidates for regulation and to what extent this can or should be internationally driven. Concern about the use of live facial recognition technologies is becoming widespread with many U.S. cities banning its use and proposals for its regulation under discussion in the European Union and the United Kingdom.

Of concern too are technologies involving deep fakes and algorithmic decision making in sensitive areas, such as criminal justice and financial services. The debate over hard and soft law in this area is by no means concluded, but there is no doubt that pooling expertise at international level could bear fruit. A common international framework informed by the work so far of the high-level panel on digital cooperation, the UN Human Rights Council, and their AI for Good platform, and brokered by UNESCO, where an expert group has been working on a recommendation on the ethics of artificial intelligence. The ITU or the United Nations itself, which in 2019 established a Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics in the Netherlands, could be created, and this could gain public trust for establishing that adopters are accountable for high-risk AI applications and at the same time allay concerns that AI and other digital technologies are being over-regulated.

Given that our aim internationally on AI governance must be to ensure that the cardinal principle is observed that AI needs to be our servant and not our master, there is cause for optimism that experts, policymakers, and regulators now recognize that they have a duty to ensure that whatever solution they adopt they recognize ascending degrees of AI risk and that policies and solutions are classified and calibrated accordingly.

Regulators themselves are now becoming more of a focus. Our House of Lords report recommended regulator training in AI ethics and risk assessment, and I believe that this will become the norm. But even if at this juncture we cannot yet identify a single body to take the work forward, there is clearly a growing common international AI agenda, and—especially I hope with the Biden administration coming much more into the action—we can all expect further progress in 2021.

Thank you.

Lord C-J: ‘Byzantine’ to ‘inclusive’: status update on UK digital ID

From Biometricupdate.com

https://www.biometricupdate.com/202108/byzantine-to-inclusive-status-update-on-uk-digital-id

The good, the bad and the puzzling elements of the UK’s digital ID project and landscape were discussed by a group of stakeholders who found the situation frustrating at present, but believe recent developments offer hope for a ‘healthy ecosystem’ of private digital identity providers and parity between physical and digital credentials. Speakers also compared UK proposals with schemes emerging elsewhere, praising the EU digital wallet approach.

The panel was convened by techUK, a trade association focusing on the potential of digital technologies, against a backdrop of recent announcements by the UK’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport such as the ‘Digital identity and attributes consultation’ into the ongoing framework underpinning the move to digital, along with the slow-moving legislation on the digital economy.

“We seem to be devising some Byzantine pyramid of governance,” said Lord Tim Clement-Jones, House of Lords Spokesperson for Digital for the Liberal Democrats of the overall UK plan for digital ID on the multiple oversight and auditing bodies proposed. And that looking at the ‘Digital identity and attributes’ documentation “will blow your mind,” such is his feeling of frustration around the topic. He believes legislation on the Digital Economy Act 2017 Part 3 should have been passed long ago allowing providers such as Yoti to bring age verification solutions to the market.

Fellow panellist Julie Dawson, Director of Regulatory and Policy at Yoti was more optimistic about the current state of affairs. She noted the fact that 3.5 million people had used the UK’s EU Exit: ID Document Check app which included biometric verification to be highly encouraging as are the Home Office sandbox trials for digital age verification. However, the lack of a solid digital ID could put British people to a disadvantage, even in the UK, if they cannot verify themselves online such as in the hiring process. Yet people performing manual identity checks are expected to verify a driving license from another country, that they have never seen before, and make a decision on it – something she finds “theatrical.”

The panel, which also featured Laura Barrowcliff, Head of Strategy at digital identity provider GBG Plc was heavily skewed towards the private sector, including the chair, Margaret Moore, Director of Citizen & Devolved Government Services at French firm Sopra Steria which has recently been awarded a contract within France’s digital ID system. They agreed that the UK needs and is developing a healthy ecosystem of digital identity providers, that the ‘consumer’ should be at the heart of the system, that the private sector is an inherently necessary part of the future digital ID landscape.

The government’s role is to establish trust by setting the standards private firms must adhere to, believes Lord Clement-Jones and that it “should be opening up government services to third party digital ID”. He is opposed to the notion of a government-run digital ID system based on the outcome of the UK’s ineffective Verify scheme.

Lord Clement-Jones considers the current flow of evidence-gathering and consultations in the UK to be a “slow waltz”, particularly in light of the recent EU proposals for a digital wallet which is “exactly what is needed” as it is “leaving it to the digital marketplace”. He believes the lack of a “solid proposal” so far by the UK government is hampering the establishment of trust.

“The real thing we have to avoid is for social media to be the arbiters of digital ID. This is why we have to move fast,” said Clement-Jones, “I do not want to be defined by Google or Facebook or Instagram in terms of who I am. Let alone TikTok.” Which is why the UK needs digital commercial providers, noted the member of the House of Lords.

Yoti’s Julie Dawson believes the EU proposals could even see the bloc leapfrogging other jurisdictions with the provision for spanning the public and private sectors. The inclusion of ‘vouching’ in the UK system, where somebody without formal identity could turn to a known registered professional to vouch for them and allow them to register some form of digital ID was found to be highly encouraging. This could make the UK system more inclusive.

Data minimization should be a key part of the UK plan, where only the necessary attribute of somebody’s ID is checked, such as whether they are over 18, compared to handing over a passport or sending a scan which contains multiple other attributes which are not necessary for the seller to see. GBG’s Laura Barrowcliff said this is a highly significant benefit of digital ID and one which, if communicated to the public, could increase support for and trust in digital ID. Any reduction in fraud associated with the use of digital ID could also help sway public opinion, though multiple panellists noted that there will always be elements of identity fraud.

Yoti’s Dawson raised a concern that the current 18-month wait until any legislation comes from the framework and consultations could become lost time to developers and hopes they continue to enhance their offerings. She also called for further transparency in the discussions happening in government departments.

Lord Clement-Jones hopes for the formation of data foundations to manage publicly-held information so the public knows where data is held and how. GBG’s Laura Barrowcliff simply called for simplicity in the ongoing development of the digital ID landscape to keep consumers at the heart so that they can understand the changes and potential and buy into the scheme as their trust grows.

Digital ID: What’s the current state-of-play in the UK?

On 22 July, as part of the #DigitalID2021 event series, techUK hosted an insightful discussion exploring the current state-of-play for digital identity in the UK and how to build public trust in digital identity technologies. The panel also examined how the UK’s progress on digital ID compares with international counterparts and set out their top priorities to support the digital identity market and facilitate wider adoption.

The panel included:

- Lord Tim Clement-Jones, House of Lords Spokesperson for Digital for the Liberal Democrats

- Margaret Moore, Director of Citizen & Devolved Government Services, Sopra Steria (Chair)

- Julie Dawson, Director of Regulatory and Policy, Yoti

- Laura Barrowcliff, Head of Strategy, GBG Plc

You can watch the full webinar here or read our summary of the key insights below:

The UK’s progress on digital identity

Opening the session, the panel discussed progress around digital identity since the start of the pandemic.

Julie Dawson raised a number of developments that indicate steps in the right direction. Before the pandemic over 3.5m EU citizens proved their settled status via the EU Settlement Scheme, whilst the JMLSG and Land Registry have both since explicitly recognised digital identity, with digital right to work checks and a Home Office sandbox on age verification technologies in alcohol sales also introduced since March last year. She also lauded the creation of the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum as a great example of joining up across government departments, such as on the topic of age assurance.

Lord Tim Clement-Jones on the other hand noted that the pace of change has remained slow. He said that the UK government needs to take concrete action and should focus on opening up government data to third party providers. He also made the point that the u-turn on the Digital Economy Act Part 3 has not as yet been rectified and so the manifesto pledge to protect children online has still to be fulfilled. Julie pointed out that legislative change in terms of the Mandatory Licensing Conditions are still needed, to enable a person to prove their age to purchase alcohol without solely requiring a physical document with a physical hologram.

Collaboration across industry around digital identities was also highlighted by Julie, drawing upon the example of the Good Health Pass Collaborative which has emerged since the start of the pandemic. The Collaborative has brought together a variety of stakeholders and over 130 companies to work on an interoperable digital identity solution to facilitate international travel post-COVID to operate at scale once more.

Examining the Government alpha Trust Framework and latest consultation

Moving on to look at the government’s alpha Trust Framework for digital identity, as well as the newly published consultation on digital identity and attributes, the panel explored what these documents do well and what gaps ultimately remain.

Julie Dawson and Laura Barrowcliff both saw a lot of good in the new proposals, with Laura highlighting how the priorities in the government’s approach around governance, inclusion and interoperability broadly hit on the right points. Julie also highlighted the role for vouching in the government’s framework as a positive step and emphasised the government’s recognition of the importance of parity for digital identity verification as one of the most central developments for wider adoption of the technology.

Providing a more cautious view, Lord Tim Clement-Jones said the UK risked creating a byzantine pyramid of governance on digital identity. He pointed to the huge number of bodies envisaged to have roles in the UK system and raised concerns that the UK will end up with a certification scheme that differs from anyone else’s internationally by not using existing standards or accreditation systems.

Looking forward, Julie highlighted that providers are looking for clarity on how to operate and deliver over the next 18 months before any of these documents become legislation. She also expressed the sincere hope that the progress made in terms of offering digital Right to Work checks, alongside physical ones, will continue rather than end in September 2021.

She identified two separate ‘tracks’ for public and private sector use of digital identity and raised the need for a conversation on when and how to join these up with the consumer at the heart. When considering data sources, for example, the ability of digital identity providers to access data across the Passport Office, the DVLA and other government agencies and departments is critical to support the development of digital identity solutions.

The panel was pleased to see the creation of a new government Digital Identity Strategy Board which they hoped would drive progress but raised the need for further transparency about ongoing work in this space, including a list of members, TOR and meeting minutes from these sessions.

Public trust in digital identity

One of the core topics of conversation centred upon trust in digital identity technologies and what steps can be taken to drive wider public trust in this space.

Lord Tim Clement-Jones said that there is a key role for government on standards to ensure digital identity providers are suitable and trustworthy, as well as in providing a workable and feasible proposal that inspires public confidence.

Julie highlighted how, alongside the Post Office, Yoti welcomed the soon to be published research undertaken by OIX into documents and inclusion.

Laura Barrowcliff emphasised the importance of context for public trust, putting the consumer experience at the heart of considerations. Opening up digital identity and consumer choice is one such way of improving the experience for users. Whilst much of the discussion on trust ties in with concerns around fraud, Laura highlighted how digital identity can actually help from a security and privacy perspective by embodying principles such as data minimisation and transparency. She also highlighted how data minimisation and proportionate use of digital identity data could be key for user buy-in.

Lessons from around the world

Looking to international counterparts, the panel drew attention to countries around the world which have made good progress on digital identity and key learnings from these global exemplars.

The progress on digital identity made in Singapore and Canada was mentioned by Julie Dawson, who emphasised the openness around digital identity proposals – which span the public and private sector – and the work being done to keep citizens informed and involve them in the process.

Julie also raised the example of the EU, which is accelerating its work on digital identity with an approach that also spans the public and private sector and is looking at key issues such as data sources whilst focusing on the consumer. Lord Tim Clement-Jones emphasised the importance of monitoring Europe’s progress in this area and the need for the UK government to consider how its own approach will be interoperable internationally.

Panellists discussed the role digital identities have played in Estonia where 99% of citizens hold digital ID and public trust in digital identities is the norm. However, they recognised key differences between the UK and Estonia. In the UK, digital identity solutions are developing in the context of widespread use of physical identification documents, whereas digital identities were the starting point in Estonia.

Beyond the EU, Laura said that GBG has a digital identity solution in Australia where the market for reusable identities is accelerating rapidly. She highlighted that working with private sector companies who have the necessary infrastructure and capabilities in place is critical to drive adoption.

Priorities for digital identity

Drawing the discussion to a close, each of the panellists were asked for their top priority to support public trust and the growth of the digital identity market in the UK.

Transparency was identified as Julie Dawson’s top priority, particularly around what discussions are happening within and across government departments and on the work of the Strategy Board.

Lord Tim-Clement Jones highlighted data and trustworthy data-sharing as key. He said he hopes to see the formation of data foundations and trusts of publicly held information that is properly curated to be used or shared on the basis of set standards and rules, which should spill over into the digital identity arena.

Laura Barrowcliff said simplicity is most important, keeping things simple for those working in the ecosystem as well as for consumers, with those consumers at the heart of all decision-making processes.

In the new era of geopolitical competition and economic rivalry, what strategies should China and the UK adopt to forge a more constructive relationship?

From Kalavinka Viewpoint #8

The prevailing mood now in Europe is to view China through a security and human rights lens rather than the trade and investment approach of the past 20 years. This has been heavily influenced by the policy of successive US administrations. People make a big mistake thinking geopolitical American policy always changes with a new administration. Not having Trump tweeting at 6am is a relief, but Joe Biden is going to be as hardline over security issues and relations with China as his predecessor. For better or worse in the UK, and to a lesser extent across the EU, having diverged for a decade, driven by the prospect of more limited access to intelligence ties, we have now decided to align ourselves more closely with US policy towards China. The UK’s recent National Security and Investment Act which identifies 17 sensitive sectors, including AI and quantum computing technologies where government can block investment transactions is a close imitation of CFIUS. So, for UK corporate investors in particular there is a new tension between investment and national security. With the new legislation and dynamics around trade, businesses will have to be politically advertent. They will have to look at whether the sector they seek investment in or to invest in in partnership with overseas investors is potentially sensitive.

Globally repatriation of supply chains will become an issue. These things ebb and flow. Over the 20th century, they expanded, shrank and expanded again. But, especially as a result of Brexit, the pandemic and people’s understanding of how the vaccinations were manufactured – and as a result of our new, much poorer relationship with China – repatriation is going to be an imperative. Going forward the best way of engaging with China and Chinese investment will be to avoid sourcing from sensitive provinces, not dealing with issues that could give rise to the sort of national infrastructure security concerns that Huawei did, and engaging positively over the essential global areas for cooperation such as the UN sustainable development goals and climate change. If we don’t, we won’t see net zero by 2050. China isn’t going to disappear as an important economic powerhouse and trading and investment partner. But we need to pick and choose where we trade and cooperate. And in this climate that will require good navigation skills.

Britain should be leading the global conversation on tech

It's been clear during the pandemic that we're increasingly dependent on digital technology and online solutions. The Culture Secretary recently set out 10 tech priorities. Some of these reflected in the Queen's Speech, but how do they measure up and are they the right ones?

First, we need to roll out world-class digital infrastructure nationwide and level up digital prosperity across the UK.

We were originally promised spending of £5bn by 2025 yet only a fraction of this - £1.2 billion - will have been spent by then. Digital exclusion and data poverty has become acute during the pandemic. It's estimated that some 1.8 million children have not had adequate digital access. It's not just about broadband being available, it's about affordability too and that devices are available.

Unlocking the power of data is another priority, as well as championing free and fair digital trade.

We recently had the government’s response to the consultation on the National Data Strategy. There is some understanding of the need to maintain public trust in the sharing and use of their data and a welcome commitment to continue with the work started by the Open Data Institute in creating trustworthy mechanisms such as data institutions and trusts to do so. But recent events involving GP held data demonstrate that we must also ensure public data is valued and used for public benefit and not simply traded away. We should establish a Sovereign Health Data Fund as suggested by Future Care Capital.

"The pace, scale and ambition of government action does not match the upskilling challenge facing many people working in the UK"

We must keep the UK safe and secure online. We need the “secure by design” consumer protection provisions now promised. But the draft Online Safety Bill now published is not yet fit for purpose. The problem is what's excluded. In particular, commercial pornography where there is no user generated content; societal harms caused for instance by fake news/disinformation so clearly described in the Report of Lord Puttnam’s Democracy and Digital Technologies Select Committee; all educational and news platforms.

Additionally, no group actions can be brought. There's no focus on the issues surrounding anonymity/know your user, or any reference to economic harms. Most tellingly, there is no focus on enhanced PHSE or the promised media literacy strategy - both of which must go hand-in-hand with this legislation. There's also little clarity on the issue of algorithmic pushing of content.

It’s vital that we build a tech-savvy nation. This is partly about digital skills for the future and I welcome greater focus on further education in the new Skills and Post-16 Education Bill. But the pace, scale and ambition of government action does not match the upskilling challenge facing many people working in the UK, as Jo Johnson recently said.

The need for a funding system that helps people to reskill is critical. Non-STEM creative courses should be valued. Careers' advice and adult education needs a total revamp. Apprentice levy reform is overdue. The work of Local Digital Skills Partnerships is welcome, but they are massively under-resourced. Broader digital literacy is crucial too, as the AI Council in their AI Roadmap pointed out. As is greater diversity and inclusion in the tech workforce.

We must fuel a new era of start-ups and scaleups and unleash the transformational power of tech and AI.

The government needs to honour their pledge to the Lords' Science and Technology Committee to support catapults to be more effective institutions as a critical part of innovation strategy. I welcome the commitment to produce a National AI Strategy, which we should all contribute to when the consultation takes place later this year.

We should be leading the global conversation on tech, the recent G7 Digital Communique and plans to host the Future Tech Forum, but we need to go beyond principles in establishing international AI governance standards and solutions. G7 agreement on a global minimum corporation tax rate bodes well for OECD digital tax discussions.

At the end of the day there are numerous notable omissions. Where is the commitment to a Bill to set up the new Digital Markets Unit, or tackling the gig economy in the many services run through digital applications? The latter should be a major priority.

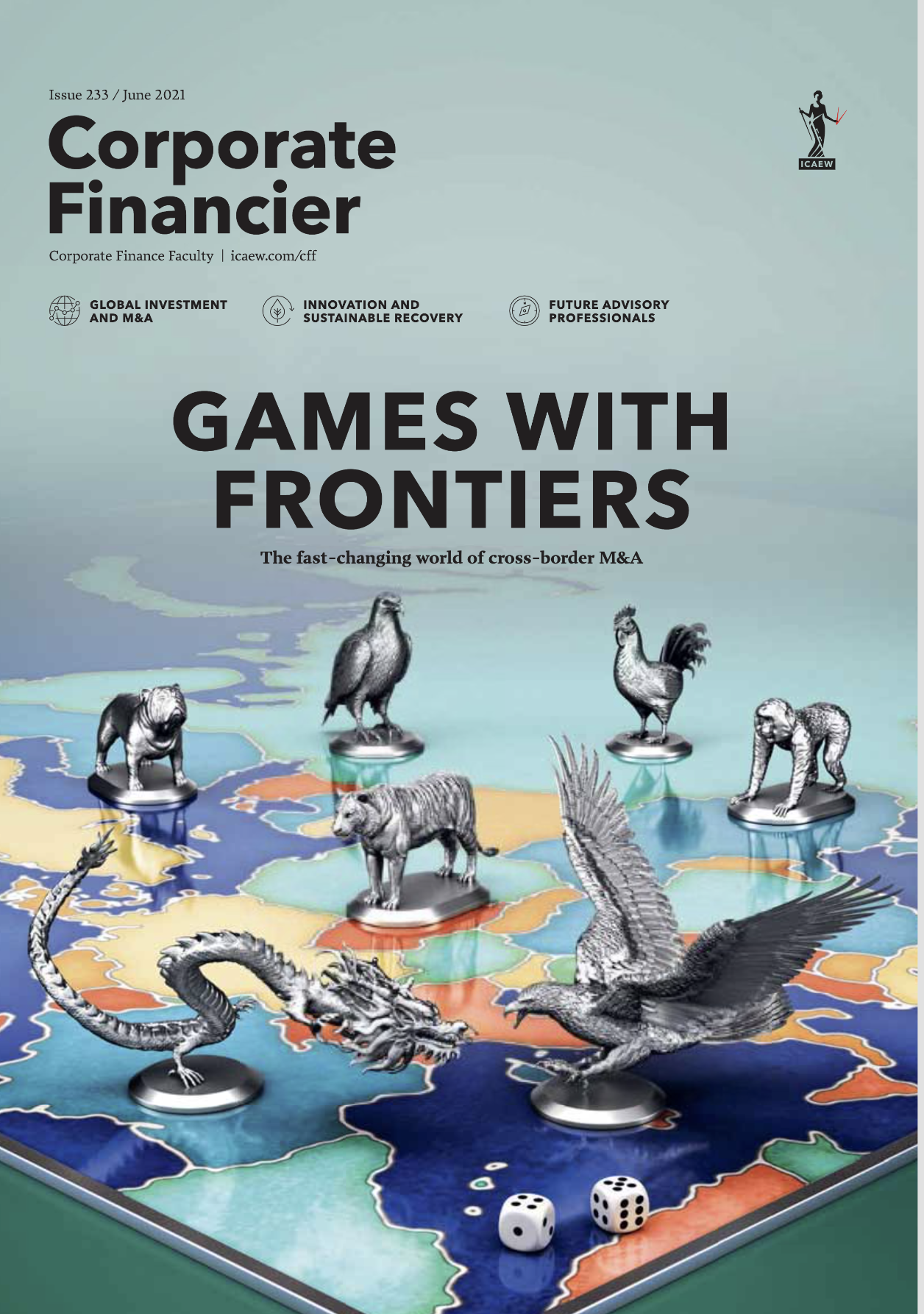

Lord C-J in the Corporate Financier on the National Security Investment Act and the new investment landscape

“People make a big mistake thinking macro American policy changes with the political parties. Not having Trump tweeting at 6am is wonderful, but Joe Biden is going to be as pragmatic over the American trade policy and is not going to suddenly rush into a deal with us.

“CFIUS has been around for an awfully long time. In a sense, you could say that our National Security and Investment Act is an imitation of CFIUS. America isn’t going to suddenly cave in on demands for agricultural imports, for instance, but again, it may be that the climate-change agenda will be more important to them.

“Then there’s the whole area of regulations. There is a rather different American culture to regulation, but now there’s more of an appetite for it around climate and the environment than there was under Trump.”

Here is the full article

These are the ingredients for good higher education governance

I recently took part in a session on "Higher education governance - the challenges that lie ahead and what can we do about it " at an AdvanceHE Clerks and Secretaries Network Event and shared my view on university governance. This is the blog I wrote afterwards which reflects what I said.

https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/ingredients-good-higher-education-governance

Chairing a Higher Education institution is a continual learning process and it was useful to reflect on governance in the run up to Advance HE’s recent discussion session with myself and Jane Hamilton, Chair of Council of the University of Essex.

Governance needs to be fit for purpose in terms of setting and adhering to a strategy for sustainable growth with a clear set of key strategic objectives and doing it by reference to a set of core values. And I entirely agree with Jane that behaviour and culture which reflect those values are as important as governance processes.

But the context is much more difficult than when I chaired the School of Pharmacy from 2008 when HEFCE was the regulator. Or even when I chaired UCL’s audit committee from 2012. The OfS is a different animal altogether and despite the assurance of autonomy in the Higher Education Act, it feels a more highly regulated and more prescribed environment than ever.

I was a Company Secretary of a FTSE 100 company for many years so I have some standard of comparison with the corporate sector! Current university governance, I believe, in addition to the strategic aspect, has two crucial overarching challenges.

First, particularly in the face of what some have described as the culture war, there is the crucial importance of making, and being able to demonstrate, public contribution through – for example – showing that:

- We have widened access

- We are a crucial component of social mobility, diversity and inclusion and enabling life chances

- We provide value for money

- We provide not just an excellent student experience but social capital and a pathway to employment as well

- In relation to FE, we are complementary and not just the privileged sibling

- We are making a contribution to post-COVID recovery in many different ways, and contributed to the ‘COVID effort’ through our expertise and voluntary activity in particular

- We make a strong community contribution especially with our local schools

- Our partnerships in research and research output make a significant difference.

All this of course needs to be much broader than simply the metrics in the Research Excellence and Knowledge Exchange Frameworks or the National Student Survey.

The second important challenge is managing risk in respect of the many issues that are thrown at us for example

- Funding: Post pandemic funding, subject mix issues-arts funding in particular. The impact of overseas student recruitment dropping. National Security and Investment Act requirements reducing partnership opportunities. Loss of London weighting. Possible fee reduction following Augar Report recommendations

- The implications of action on climate change

- USS pension issues

- Student welfare issues such as mental health and digital exclusion

- Issues related to the Prevent programme

- Ethical Investment in general, Fossil Fuels in particular

- And, of course, freedom of speech issues brought to the fore by the recent Queen’s Speech.

This is not exhaustive as colleagues involved in higher education will testify! There is correspondingly a new emphasis on enhanced communication in both areas given what is at stake.

In a heavily regulated sector there is clearly a formal requirement for good governance in our institutions and processes and I think it’s true to say, without being complacent, that Covid lockdowns have tested these and shown that they are largely fit for purpose and able to respond in an agile way. We ourselves at Queen Mary, when going virtual, instituted a greater frequency of meetings and regular financial gateways to ensure the Council was fully on top of the changing risks. We will all, I know, want to take some of the innovations forward in new hybrid processes where they can be shown to contribute to engagement and inclusion.

But Covid has also demonstrated how important informal links are in terms of understanding perspectives and sharing ideas. Relationships are crucial and can’t be built and developed in formal meetings alone. This is particularly the case with student relations. Informal presentations by sabbaticals can reap great rewards in terms of insight and communication. More generally, it is clear that informal preparatory briefings for members can be of great benefit before key decisions are made in a formal meeting.

External members have a strong part to play in the expertise and perceptions they have, in the student employability agenda and the relationships they build within the academic community and harnessing these in constructive engagement is an essential part of informal governance.

So going forward what is and should be the state of university governance? There will clearly be the need for continued agility and there will be no let-up in the need to change and adapt to new challenges. KPI’s are an important governance discipline but we will need to review the relevance of KPIs at regular intervals. We will need to engage with an ever wider group of stakeholders, local, national and global. All of our ‘civic university’ credentials may need refreshing.

The culture will continue to be set by VCs to a large extent, but a frank and open “no surprises” approach can be promoted as part of the institution’s culture. VCs have become much more accountable than in the past. Fixed terms and 360 appraisals are increasingly the norm.

The student role in co-creation of courses and the educational experience is ever more crucial. The quality of that experience is core to the mission of HE institutions, so developing a creative approach to the rather anomalous separate responsibilities of senate and council is needed.

Diversity on the Council in every sense is fundamental so that there are different perspectives and constructive challenge to the leadership. 1-2-1s with all council members on a regular basis to gain feedback and talk about their contribution and aspirations are important. At Council meetings we need to hear from not just the VC, but the whole senior executive team and heads of school: distributed leadership is crucial.

Given these challenges, how do we attract the best council members? Should we pay external members? Committee chairs perhaps could receive attendance allowance type payments. But I would prefer it if members can be recruited who continue to want to serve out of a sense of mission.

This will very much depend on how the mission and values are shared and communicated. So we come back to strategic focus, and the central role of governance in delivering it!