Lord C-J : We must put the highest duties on small risky sites

Many of us were horrified that the regulations implementing the provisions of the Online Safety Act proposed by the government on the advice of Ofcom did not put sites such as Telegram, 4Chan and 8Chan in the top category-Category 1-for duties under the Act .

As a result I tabled a regret motion:

" that this House regrets that the Regulations do not impose duties available under the parent Act on small, high-risk platforms where harmful content, often easily accessible to children, is propagated; calls on the Government to clarify which smaller platforms will no longer be covered by Ofcom’s illegal content code and which measures they will no longer be required to comply with; and calls on the Government to withdraw the Regulations and establish a revised definition of Category 1 services.”

This is what I said in opening the debate. The motion passed against the government by 86 to 55.

Those of us who were intimately involved with its passage hoped that the Online Safety Act would bring in a new era of digital regulation, but the Government’s and Ofcom’s handling of small but high-risk platforms threatens to undermine the Act’s fundamental purpose of creating a safer online environment. That is why I am moving this amendment, and I am very grateful to all noble Lords who are present and to those taking part.

The Government’s position is rendered even more baffling by their explicit awareness of the risks. Last September, the Secretary of State personally communicated concerns to Ofcom about the proliferation of harmful content, particularly regarding children’s access. Despite this acknowledged awareness, the regulatory framework remains fundamentally flawed in its approach to platform categorisation.

The parliamentary record clearly shows that cross-party support existed for a risk-based approach to platform categorisation, which became enshrined in law. The amendment to Schedule 11 from the noble Baroness, Lady Morgan—I am very pleased to see her in her place—specifically changed the requirement for category 1 from a size “and” functionality threshold to a size “or” functionality threshold. This modification was intended to ensure that Ofcom could bring smaller, high-risk platforms under appropriate regulatory scrutiny.

Subsequently, in September 2023, on consideration of Commons amendments, the Minister responsible for the Bill, the noble Lord, Lord Parkinson—I am pleased to see him in his place—made it clear what the impact was:

“I am grateful to my noble friend Lady Morgan of Cotes for her continued engagement on the issue of small but high-risk platforms. The Government were happy to accept her proposed changes to the rules for determining the conditions that establish which services will be designated as category 1 or 2B services. In making the regulations, the Secretary of State will now have the discretion to decide whether to set a threshold based on either the

number of users or the functionalities offered, or on both factors. Previously, the threshold had to be based on a combination of both”.—[Official Report, 19/9/23; col. 1339.

I do not think that could be clearer.

This Government’s and Ofcom’s decision to ignore this clear parliamentary intent is particularly troubling. The Southport tragedy serves as a stark reminder of the real-world consequences of inadequate online regulation. When hateful content fuels violence and civil unrest, the artificial distinction between large and small platforms becomes a dangerous regulatory gap. The Government and Ofcom seem to have failed to learn from these events.

At the heart of this issue seems to lie a misunderstanding of how harmful content proliferates online. The impact on vulnerable groups is particularly concerning. Suicide promotion forums, incel communities and platforms spreading racist content continue to operate with minimal oversight due to their size rather than their risk profile. This directly contradicts the Government’s stated commitment to halving violence against women and girls, and protecting children from harmful content online. The current regulatory framework creates a dangerous loophole that allows these harmful platforms to evade proper scrutiny.

The duties avoided by these smaller platforms are not trivial. They will escape requirements to publish transparency reports, enforce their terms of service and provide user empowerment tools. The absence of these requirements creates a significant gap in user protection and accountability.

Perhaps the most damning is the contradiction between the Government’s Draft Statement of Strategic Priorities for Online Safety, published last November, which emphasises effective regulation of small but risky services, and their and Ofcom’s implementation of categorisation thresholds that explicitly exclude these services from the highest level of scrutiny. Ofcom’s advice expressly disregarded—“discounted” is the phrase it used—the flexibility brought into the Act via the Morgan amendment, and advised that regulations should be laid that brought only large platforms into category 1. Its overcautious interpretation of the Act creates a situation where Ofcom recognises the risks but fails to recommend for itself the full range of tools necessary to address them effectively.

This is particularly important in respect of small, high-risk sites, such as suicide and self-harm sites, or sites which propagate racist or misogynistic abuse, where the extent of harm to users is significant. The Minister, I hope, will have seen the recent letter to the Prime Minister from a number of suicide, mental health and anti-hate charities on the issue of categorisation of these sites. This means that platforms such as 4chan, 8chan and Telegram, despite their documented role in spreading harmful content and co-ordinating malicious activities, escaped the full force of regulatory oversight simply due to their size. This creates an absurd situation where platforms known to pose significant risks to public safety receive less scrutiny than large platforms with more robust safety measures already in place.

The Government’s insistence that platforms should be “safe by design”, while simultaneously exempting high-risk platforms from category 1 requirements based

solely on size metrics, represents a fundamental contradiction and undermines what we were all convinced—and still are convinced—the Act was intended to achieve. Dame Melanie Dawes’s letter, in the aftermath of Southport, surely gives evidence enough of the dangers of some of the high-risk, smaller platforms.

Moreover, the Government’s approach fails to account for the dynamic nature of online risks. Harmful content and activities naturally migrate to platforms with lighter regulatory requirements. By creating this two-tier system, they have, in effect, signposted escape routes for bad actors seeking to evade meaningful oversight. This short-sighted approach could lead to the proliferation of smaller, high-risk platforms designed specifically to exploit these regulatory gaps. As the Minister mentioned, Ofcom has established a supervision task force for small but risky services, but that is no substitute for imposing the full force of category 1 duties on these platforms.

The situation is compounded by the fact that, while omitting these small but risky sites, category 1 seems to be sweeping up sites that are universally accepted as low-risk despite the number of users. Many sites with over 7 million users a month—including Wikipedia, a vital source of open knowledge and information in the UK—might be treated as a category 1 service, regardless of actual safety considerations. Again, we raised concerns during the passage of the Bill and received ministerial assurances. Wikipedia is particularly concerned about a potential obligation on it, if classified in category 1, to build a system that allows verified users to modify Wikipedia without any of the customary peer review.

Under Section 15(10), all verified users must be given an option to

“prevent non-verified users from interacting with content which that user generates, uploads or shares on the service”.

Wikipedia says that doing so would leave it open to widespread manipulation by malicious actors, since it depends on constant peer review by thousands of individuals around the world, some of whom would face harassment, imprisonment or physical harm if forced to disclose their identity purely to continue doing what they have done, so successfully, for the past 24 years.

This makes it doubly important for the Government and Ofcom to examine, and make use of, powers to more appropriately tailor the scope and reach of the Act and the categorisations, to ensure that the UK does not put low-risk, low-resource, socially beneficial platforms in untenable positions.

There are key questions that Wikipedia believes the Government should answer. First, is a platform caught by the functionality criteria so long as it has any form of content recommender system anywhere on UK-accessible parts of the service, no matter how minor, infrequently used and ancillary that feature is?

Secondly, the scope of

“functionality for users to forward or share regulated user-generated content on the service with other users of that service”

is unclear, although it appears very broad. The draft regulations provide no guidance. What do the Government mean by this?

Thirdly, will Ofcom be able to reliably determine how many users a platform has? The Act does not define “user”, and the draft regulations do not clarify how the concept is to be understood, notably when it comes to counting non-human entities incorporated in the UK, as the Act seems to say would be necessary.

The Minister said in her letter of 7 February that the Government are open to keeping the categorisation thresholds under review, including the main consideration for category 1, to ensure that the regime is as effective as possible—and she repeated that today. But, at the same time, the Government seem to be denying that there is a legally robust or justifiable way of doing so under Schedule 11. How can both those propositions be true?

Can the Minister set out why the regulations, as drafted, do not follow the will of Parliament—accepted by the previous Government and written into the Act—that thresholds for categorisation can be based on risk or size? Ofcom’s advice to the Secretary of State contained just one paragraph explaining why it had ignored the will of Parliament—or, as the regulator called it, the

“recommendation that allowed for the categorisation of services by reference exclusively to functionalities and characteristics”.

Did the Secretary of State ask to see the legal advice on which this judgment was based? Did DSIT lawyers provide their own advice on whether Ofcom’s position was correct, especially in the light of the Southport riots?

How do the Government intend to assess whether Ofcom’s regulatory approach to small but high-harm sites is proving effective? Have any details been provided on Ofcom’s schedule of research about such sites? Do the Government expect Ofcom to take enforcement action against small but high-harm sites, and have they made an assessment of the likely timescales for enforcement action?

What account did the Government and Ofcom take of the interaction and interrelations between small and large platforms, including the use of social priming through online “superhighways”, as evidenced in the Antisemitism Policy Trust’s latest report, which showed that cross-platform links are being weaponised to lead users from mainstream platforms to racist, violent and anti-Semitic content within just one or two clicks?

The solution lies in more than mere technical adjustments to categorisation thresholds; it demands a fundamental rethinking of how we assess and regulate online risk. A truly effective regulatory framework must consider both the size and the risk profile of platforms, ensuring that those capable of causing significant harm face appropriate scrutiny regardless of their user numbers and are not able to do so. Anything less—as many of us across the House believe, including on these Benches—would bring into question whether the Government’s commitment to online safety is genuine. The Government should act decisively to close these regulatory gaps before more harm occurs in our increasingly complex online landscape. I beg to move.

Lords Debate Regulators : Who Watches the Watchdogs?

Recently the Lords held a debate on the report of the Industry and Regulators Select Committee (on which I sit) entitled "Who Watches the Watchdogs" about the scrutiny given to the performance independence and competence of our regulators

This is what I said. It was an opportunity as ever to emphasize that Regulation is not the enemy of innovation, or indeed growth, but can in fact, by providing certainty of standards, be the platform for it.

The Grenfell report and today’s Statement have been an extremely sobering reminder of the importance of effective regulation and the effective oversight of regulators. The principal job of regulation is to ensure societal safety and benefit—in essence, mitigating risk. In that context, the performance of the UK regulators, as well as the nature of regulation, is crucial.

In the early part of this year, the spotlight was on regulation and the effectiveness of our regulators. Our report was followed by a major contribution to the debate from the Institute for Government. We then had the Government’s own White Paper, Smarter Regulation, which seemed designed principally to take the growth duty established in 2015 even further with a more permissive approach to risk and a “service mindset”, and risked creating less clarity with yet another set of regulatory principles going beyond those in the Better Regulation Framework and the Regulators’ Code.

Our report was, however, described as excellent by the Minister for Investment and Regulatory Reform in the Department for Business and Trade under the previous Government, the noble Lord, Lord Johnson of Lainston, whom I am pleased to see taking part in the debate today. I hope that the new Government will agree with that assessment and take our recommendations further forward.

Both we and the Institute for Government identified a worrying lack of scrutiny of our regulators—indeed, a worrying lack of even identifying who our regulators are. The NAO puts the number of regulators at around 90 and the Institute for Government at 116, but some believe that there are as many as 200 that we need to take account of. So it is welcome that the previous Government’s response said that a register of regulators, detailing all UK regulators, their roles, duties and sponsor departments, was in the offing. Is this ready to be launched?

The crux of our report was to address performance, strategic independence and oversight of UK regulators. In exploring existing oversight, accountability measures and the effectiveness of parliamentary oversight, it was clear that we needed to improve self-reporting by regulators. However, a growth duty performance framework, as proposed in the White Paper, does not fit the bill.

Regulators should also be subject to regular performance evaluations, as we recommended; these reviews should be made public to ensure transparency and accountability. To ensure that these are effective, we recommended, as the noble Lord, Lord Hollick mentioned, establishing a new office for regulatory performance—an independent statutory body analogous to the National Audit Office—to undertake regular performance reviews of regulators and to report to Parliament. It was good to see that, similar to our proposal, the Institute for Government called for a regulatory oversight support unit in its subsequent report, Parliament and Regulators.

As regards independence, we had concerns about the potential politicisation of regulatory appointments. Appointment processes for regulators should be transparent and merit-based, with greater parliamentary scrutiny to avoid politicisation. Although strategic guidance from the Government is necessary, it should not compromise the operational independence of regulators.

What is the new Government’s approach to this? Labour’s general election manifesto emphasised fostering innovation and improving regulation to support economic growth, with a key proposal to establish a regulatory innovation office in order to streamline regulatory processes for new technologies and set targets for tech regulators. I hope that that does not take us down the same trajectory as the previous Government. Regulation is not the enemy of innovation, or indeed growth, but can in fact, by providing certainty of standards, be the platform for it.

At the time of our report, the IfG rightly said:

“It would be a mistake for the committee to consider its work complete … new members can build on its agenda in their future work, including by fleshing out its proposals for how ‘Ofreg’ would work in practice”.

We should take that to heart. There is still a great deal of work to do to make sure that our regulators are clearly independent of government, are able to work effectively, and are properly resourced and scrutinised. I hope that the new Government will engage closely with the committee in their work.

Lords Committee Highly Critical of Office for Students

Shortly before parliament dissolved for the General Election the Housse of Lords debated the Report of the Industry and Regulators Committee Must do better: the Office for Students and the looming crisis facing higher education

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5803/ldselect/ldindreg/246/24602.htm

This is is what I said:

I declare an interest as chair of the council of Queen Mary University of London. I thank the noble Baroness, Lady Taylor, for her comprehensive and very fair introduction to our report. I thank her too for her excellent marshalling of our committee, with the noble Lord, Lord Hollick, and I add my thanks to our clerks and our special adviser during the inquiry.

I will speak in general terms rather than specifically about my own university. In higher education, there have been challenges aplenty to keep vice-chancellors and governing bodies awake at night: coming through the pandemic, industrial relations, cost of living rises for our students, pensions and research funding, to name but a few. But above all there are the ever-eroding unit of resource for domestic students, which was highlighted extremely effectively by the noble Lord, Lord Johnson of Marylebone, on the “Today” programme last week, and the Government’s continual policy interventions, including, above all, their seeming determination to reduce overseas student numbers.

In the face of this, I have to keep reminding myself that in 2021-22 Queen Mary University delivered a total economic benefit to the UK economy of £4.4 billion. For every pound we spent in 2021-22, we generated £7 of economic benefit. Universities are some of our great national assets. They not only are intellectual powerhouses for learning, education and social mobility, making a huge contribution to their local communities, but are inextricably linked to our national prospects for innovation and economic growth.

The committee’s report was very well received outside this House. Commentating in Wonkhe, the higher education blog—I do not know whether there are many readers of it around; I suspect there are—on the government and OfS responses to our report, its deputy editor noted:

“If you were expecting a seasonal mea culpa from either the regulator or the government … on any of these, it is safe to say that you will be disappointed”.

For him, the four standout aspects of our report were:

“the revelations about the place of students in the Office for Students … the criticism of the perceived closeness of the independent regulator to the government of the day … the school playground

level approach to the Designated Quality Body question … and the less splashy but deeply concerning suggestion that OfS didn’t really understand the financial problems the sector was facing”.

As regards the DQB question, which the committee explored in some depth, the current approach being taken by the OfS is extremely opaque. We clearly need a regulatory approach to quality to align with international standards. It is clear that the quickest way to get the English system realigned with international good practice would be to reinstate the QAA—an internationally recognised agency. Most of us cannot understand what seems to be the implacable hostility of the OfS to the QAA.

It is notable that the OfS, perhaps stung by the committee’s report, has now belatedly woken up to the fragility of the sector’s financial model and the fact that the future of the overseas student intake is central to financial underpinning. In its 2023 report on the financial sustainability of HE providers, the OfS confirmed that the

“overreliance on international student recruitment is a material risk for many types of providers where a sudden decline or interruption to international fees could trigger sustainability concerns”

and

“result in some providers having to make significant changes to their operating model or face a material risk of closure”.

Advice that they need to change their funding model and diversify their revenue streams is not particularly helpful, given the options available.

The Migration Advisory Committee’s Rapid Review of the Graduate Route, published last week—which recommends retaining the graduate visa on its current terms and reports that the graduate route is achieving the objectives set for it by the Government, finding

“no evidence of any significant abuse”—

is therefore of crucial importance. There is absolutely no doubt about the importance of the work study visa to the sector and the broader UK economy. In answer to the question from the noble Lord, Lord Parekh, we want it, and I hope that the OfS will play its part in trying to persuade the Government to retain it.

The Wonkhe blog also asks the fundamental question about the Government’s response regarding the regulatory burden on higher education. I hope the Minister can tell us: do the Government think it necessary and acceptable to keep ratcheting up regulation on universities? We are going in the wrong direction. Additional resource is required to monitor and provide returns in a whole variety of areas, such as the new freedom of speech requirements.

With the extraordinary contribution that universities make to society, communities and the economy as a whole, will university regulation benefit from the proposals set out in Smarter Regulation: Delivering a Regulatory Environment for Innovation, Investment and Growth, the Government’s recent White Paper? We will discuss this in a future debate on the response to our subsequent report, Who Watches the Watchdogs? For instance, the White Paper proposes the adoption of

“a culture of world-class service”

in how regulators undertake their day-to-day activities, and the adoption by all government departments of the

“10 principles of smarter regulation”.

It says:

“All government departmental annual reports must also set out the total costs and benefits of each significant regulation introduced that year”,

and says that the Government will

“strengthen the role of the Regulatory Policy Committee and the Better Regulation Framework, improve the assessment and scrutiny of the costs of regulation, and encourage non-regulatory alternatives”.

It says:

“The government will launch a Regulators Council to improve strategic dialogue between regulators and government, alongside monitoring the effectiveness of policy and strategic guidance issued”.

Finally, it says that

“it is up to the government to better assess its regulatory agenda, to try to understand the cost of its regulation on business and society”.

What is not to like, in the context of higher education regulation? Will all this be applied to the work of the OfS?

That all said, I welcome some of the way in which the OfS, if not the Government, has responded to our report. There is an air approaching contrition, in particular regarding engagement with both students and higher education providers. I welcome the OfS reviewing its approach to student engagement, empowering the student panel to raise issues that are important to students and increasing engagement with universities and colleges to improve sector relations

As regards the Government, a dialling down of their rhetoric continually undermining higher education, a pledge to ration ministerial directions given to the OfS, and putting university finances on a more sustainable, long-term footing would be welcome.

It is clear that continued scrutiny and evaluation— I very much liked what the noble Baroness, Lady Taylor, had to say about post-scrutiny reporting—will be essential to ensure that both government and OfS actions after their responses effectively address the underlying issues raised in our report. Sad to say, I do not think that the sector is holding its breath in the meantime.

We Need a New Offence of Digital ID Theft

As part of the debates on the Data Protection Bill I recently advocated for a new Digital ID theft offence . This is what i said.

It strikes me as rather extraordinary that we do not have an identity theft offence. This is the Metropolitan Police guidance for the public:

“Your identity is one of your most valuable assets. If your identity is stolen, you can lose money and may find it difficult to get loans, credit cards or a mortgage. Your name, address and date of birth provide enough information to create another ‘you’”.

It could not be clearer. It goes on:

“An identity thief can use a number of methods to find out your personal information and will then use it to open bank accounts, take out credit cards and apply for state benefits in your name”.

It then talks about the signs that you should look out for, saying:

“There are a number of signs to look out for that may mean you are or may become a victim of identity theft … If you think you are a victim of identity theft or fraud, act quickly to ensure you are not liable for any financial losses … Contact CIFAS (the UK’s Fraud Prevention Service) to apply for protective registration”.

However, there is no criminal offence.

Interestingly enough, I mentioned this to the noble Baroness, Lady Morgan; Back in October 2022, her committee—the Fraud Act 2006 and Digital Fraud Committee—produced a really good report, Fighting Fraud: Breaking the Chain, which said:

“Identity theft is often a predicate action to the criminal offence of fraud, as well as other offences including organised crime and terrorism, but it is not a criminal offence. Cifas datashows that cases of identity fraud increased by 22% in 2021, accounting for 63% of all cases recorded to Cifas’ National Fraud Database”.

It goes on to talk about identity theft to some good effect but states:

“In February 2022, the Government confirmed that there were no plans to introduce a new criminal offence of identity theft as ‘existing legislation is in place to protect people’s personal data and prosecute those that commit crimes enabled by identity theft’”.

I do not think the committee agreed with that at all. It said:

“The Government should consult on the introduction of legislation to create a specific criminal offence of identity theft. Alternatively, the Sentencing Council should consider including identity theft as a serious aggravating factor in cases of fraud”.

The Government are certainly at odds with the Select Committee chaired by the noble Baroness, Lady Morgan. I am indebted to a creative performer called Bennett Arron, who raised this with me some years ago. He related with some pain how he took months to get back his digital identity. He said: “I eventually, on my own, tracked down the thief and gave his name and address to the police. Nothing was done. One of the reasons the police did nothing was because they didn’t know how to charge him with what he had done to me”. That is not a good state of affairs. Then we heard from Paul Davis, the head of fraud prevention at TSB. The headline of the piece in the Sunday Times was: “I’m head of fraud at a bank and my identity was still stolen”. He is top dog in this area, and he has been the subject of identity theft.

This seems an extraordinary situation, whereby the Government are sitting on their hands. There is a clear issue with identity theft, yet they are refusing—they have gone into print, in response to the committee chaired by the noble Baroness, Lady Morgan—and saying, “No, no, we don’t need anything like that; everything is absolutely fine”. I hope that the Minister can give a better answer this time around.

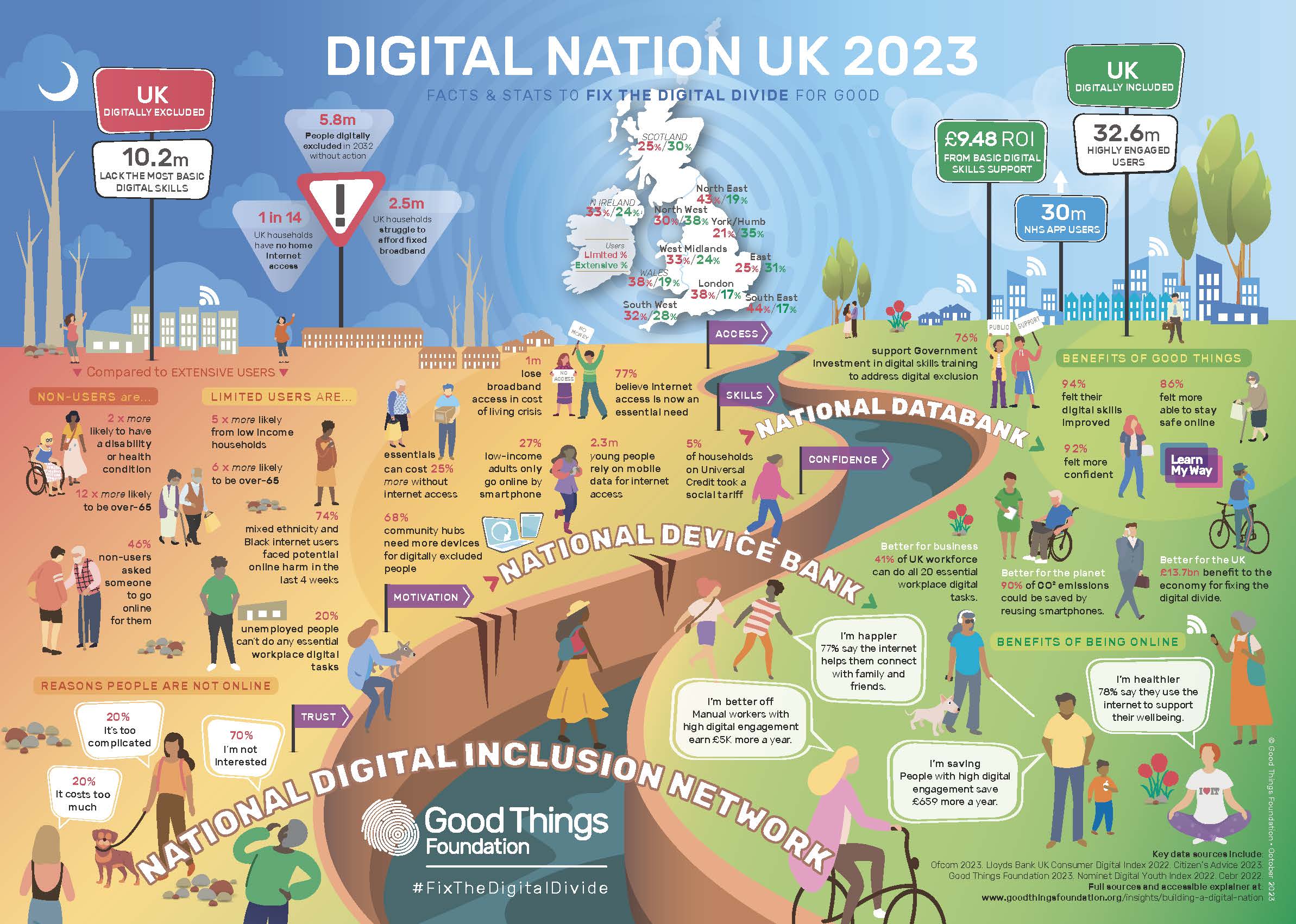

Lords call for action on Digital Exclusion

The House of Lords recently debated the Report of the Communication and Digital Committee on Digital exclusion . This is an editred version of what I said when winding up the debate.

Trying to catch up with digital developments is a never-ending process, and the theme of many noble Lords today has been that the sheer pace of change means we have to be a great deal more active in what we are doing in terms of digital inclusion than we are being currently.

Access to data and digital devices affects every aspect of our lives, including our ability to learn and work; to connect with online public services; to access necessary services, from banking, to healthcare; and to socialise and connect with the people we know and love. For those with digital access, particularly in terms of services, this has been hugely positive- as access to the full benefits of state and society has never been more flexible or convenient if you have the right skills and the right connection.

However, a great number of our citizens cannot get take advantage of these digital benefits. They lack access to devices and broadband, and mobile connectivity is a major source of data poverty and digital exclusion. This proved to be a major issue during the Covid pandemic. Of course the digital divide has not gone away subsequently—and it does not look as though it is going to any time soon.

There are new risks coming down the track, too, in the form of BT’s Digital Voice rollout. The Select Committee’s report highlighted the issues around digital exclusion. For example, it said that 1.7 million households had no broadband or mobile internet access in 2021; that 2.4 million adults were unable to complete a single basic task to get online; and that 5 million workers were likely to be acutely underskilled in basic skills by 2030. The Local Government Association’s report, The Role of Councils in Tackling Digital Exclusion, showed a very strong relationship between having fixed broadband and higher earnings and educational achievement, such as being able to work from home or for schoolwork.

To conflate two phrases that have been used today, this may be a Cinderella issue but “It’s the economy, stupid”. To borrow another phrase used by the noble Baroness, Lady Lane-Fox, we need to double down on what we are already doing. As the committee emphasised, we need an immediate improvement in government strategy and co-ordination. The Select Committee highlighted that the current digital inclusion strategy dates from 2014. They called for a new strategy, despite the Government’s reluctance. We need a new framework with national-level guidance, resources and tools that support local digital inclusion initiatives.

The current strategy seems to be bedevilled by the fact that responsibility spans several government departments. It is not clear who—if anyone—at ministerial and senior officer level has responsibility for co-ordinating the Government’s approach. Lord Foster mentioned accountability, and Lady Harding, talked about clarity around leadership. Whatever it is, we need it.

Of course, in its report, the committee stressed the need to work with local authorities. A number of noble Lords have talked today about regional action, local delivery, street-level initiatives: whatever it is, again, it needs to be at that level. As part of a properly resourced national strategy, city and county councils and community organisations need to have a key role.

The Government too should play a key role, in building inclusive digital local economies. However, it is clear that there is very little strategic guidance to local councils from central government around tackling digital exclusion. As the committee also stresses, there is a very important role for competition in broadband rollout, especially in terms of giving assurance that investors in alternative providers to the incumbents get the reassurance that their investment is going on to a level playing field. I very much hope that the Minister will affirm the Government’s commitment to those alternative providers in terms of the delivery of the infrastructure in the communications industry.

Is it not high time that we upgraded the universal service obligation? The committee devoted some attention to this and many of us have argued for this ever since it was put into statutory form. It is a wholly inadequate floor. We all welcome the introduction of social tariffs for broadband, but the question of take-up needs addressing. The take-up is desperately low at 5%. We need some form of social tariff and data voucher auto-enrolment. The DWP should work with internet service providers to create an auto-enrolment scheme that includes one or both products as part of its universal credit package. Also, of course, we should lift VAT, as the committee recommended, and Ofcom should be empowered to regulate how and where companies advertise their social tariffs.

We also need to make sure that consumers are not driven into digital exclusion by mid-contract price rises. I would very much appreciate hearing from the Minister on where we are with government and Ofcom action on this.

The committee rightly places emphasis on digital skills, which many noble Lords have talked about. These are especially important in the age of AI. We need to take action on digital literacy. The UK has a vast digital literacy skills and knowledge gap. I will not quote Full Fact’s research, but all of us are aware of the digital literacy issues. Broader digital literacy is crucial if we are to ensure that we are in the driving seat, in particular where AI is concerned. There is much good that technology can do, but we must ensure that we know who has power over our children and what values are in play when that power is exercised. This is vital for the future of our children, the proper functioning of our society and the maintenance of public trust. Since media literacy is so closely linked to digital literacy, it would be useful to hear from the Minister where Ofcom is in terms of its new duties under the Online Safety Act.

We need to go further in terms of entitlement to a broader digital citizenship. Here I commend an earlier report of the committee, Free For All? Freedom of Expression in the Digital Age. It recommended that digital citizenship should be a central part of the Government’s media literacy strategy, with proper funding. Digital education in schools should be embedded, covering both digital literacy and conduct online, aimed at promoting stability and inclusion and how that can be practised online. This should feature across subjects such as computing, PSHE and citizenship education, as recommended by the Royal Society for Public Health in its #StatusOfMind report as long ago as 2017.

Of course, we should always make sure that the Government provide an analogue alternative. We are talking about digital exclusion but, for those who are excluded and have the “fear factor”, we need to make sure and not assume that all services can be delivered digitally.

Finally, we cannot expect the Government to do it all. We need to draw on and augment our community resources; I am a particular fan of the work of the Good Things Foundation See their info graphic accompanying this) FutureDotNow, CILIP—the library and information association—and the Trussell Trust, and we have heard mention of the churches, which are really important elements of our local delivery. They need our support, and the Government’s, to carry on the brilliant work that they do.

We Can't Let this Disastrous Retained EU Law Bill go through in its current form

In the Lords we recently saw the arrival of the Retained EU (Law Revocation and Reform ) Bill. With its sunset clause threatening to phase out up to 4000 pieces of vital IP, environmental, consumer protection and product safety legislation on 31st December 2023 we need to drastically change or block it. This is what I said on second reading

I hosted a meeting with Zsuzsanna Szelényi, the brave Hungarian former MP, a member of Fidesz and the author of Tainted Democracy: Viktor Orbán and the Subversion of Hungary. I reflected that this Bill, especially in the light of the reports from the DPRRC and the SLSC, is a government land grab of powers over Parliament, fully worthy of Viktor Orbán himself and his cronies. This is no less than an attempt to achieve a tawdry version of Singapore-on-Thames in the UK without proper democratic scrutiny, to the vast detriment of consumers, workers and creatives. It is no surprise that the Regulatory Policy Committee has stated that the Bill’s impact assessment is not fit for purpose.

It is not only important regulations that are being potentially swept away, but principles of interpretation and case law, built up over nearly 50 years of membership of the EU. This Government are knocking down the pillars of certainty of application of our laws. Lord Fox rightly quoted the Bar Council in this respect. Clause 5 would rip out the fundamental right to the protection of personal data from the UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018. This is a direct threat to the UK’s data adequacy, with all the consequences that that entails. Is that really the Government’s intention?

As regards consumers, Which? has demonstrated the threat to basic food hygiene requirements for all types of food businesses: controls over meat safety, maximum pesticide levels, food additive regulations, controls over allergens in foods and requirements for baby foods. Product safety rights at risk include those affecting child safety and regulations surrounding transport safety. Civil aviation services could be sunsetted, along with airlines’ liability requirements in the event of airline accidents. Consumer rights on cancellation and information, protection against aggressive selling practices and redress for consumer law breaches across many sectors could all be impacted. Are any of these rights dispensable—mere parking tickets?

The TUC and many others have pointed out the employment rights that could be lost, and health and safety requirements too. Without so much as a by-your-leave, the Government could damage the employment conditions of every single employee in this country.

For creative workers in particular, the outlook as a result of this Bill is bleak. The impact of any change on the protection of part-time and fixed-term workers is particularly important for freelance workers in the creative industries. Fixed-term workers currently have the right to be treated no less favourably than a comparable permanent employee unless the employer can justify the different treatment. Are these rights dispensable? Are they mere parking tickets?

Then there is potentially the massive change to intellectual property rights, including CJEU case law on which rights holders rely. If these fall away, it creates huge uncertainty and incentive for litigation. The IP regulations and case law on the dashboard which could be sunsetted encompass a whole range, from databases, computer programs and performing rights to protections for medicines. At particular risk are artists’ resale rights, which give visual artists and their heirs a right to a royalty on secondary sales of the artist’s original works when sold on the art market. Visual artists are some of the lowest-earning creators, earning between £5,000 and £10,000 a year. Are these rights dispensable? Have the Government formed any view at all yet?

This Bill has created a fog of uncertainty over all these areas—a blank sheet of paper, per Lord Beith; a giant question mark, per Lord Heseltine—and the impact could be disastrous. I hope this House ensures it does not see the light of day in its current form.

Crossparty work yet to do on the Online Safety Bill

Finally the Online Safety Bill has arrived in the House of Lords. This is what I said on winding up at the end of the debate which had 66 speakers in total, many of them making passionate and moving speeches. We all want to see this go through, in particular to ensure that children and vulnerable adults are properly protected on social media, but there are still changes we want to see before it comes into law.

My Lords, I thank the Minister for his detailed introduction and his considerable engagement on the Bill to date. This has been a comprehensive, heartfelt and moving debate, with a great deal of cross-party agreement about how we must regulate social media going forward. With 66 speakers, however, I sadly will not be able to mention many significant contributors by name.

It has been a long and winding road to get to this point, as noble Lords have pointed out. As the Minister pointed out, along with a number of other noble Lords today, I sat on the Joint Committee which reported as far back as December 2021. I share the disappointment of many that we are not further along with the Bill. It is still a huge matter of regret that the Government chose not to implement Part 3 of the DEA in 2019. Not only, as mentioned by many, have we had a cavalcade of five Culture Secretaries, we have diverged a long way from the 2019 White Paper with its concept of the overarching duty of care. I share the regret that the Government have chosen to inflict last-minute radical surgery on the Bill to satisfy the, in my view, unjustified concerns of a very small number in their own party.

Ian Russell—I pay tribute to him, like other noble Lords—and the Samaritans are right that this is a major watering down of the Bill. Mr Russell showed us just this week how Molly had received thousands and thousands of posts, driven at her by the tech firms’ algorithms, which were harmful but would still be classed as legal. The noble Lord, Lord Russell, graphically described some of that material. As he said, if the regulator does not have powers around that content, there will be more tragedies like Molly’s.

The case for proper regulation of harms on social media was made eloquently to us in the Joint Committee by Ian and by witnesses such Edleen John of the FA and Frances Haugen, the Facebook whistleblower. The introduction to our report makes it clear that the key issue is the business model of the platforms, as described by the noble Lords, Lord Knight and Lord Mitchell, and the behaviour of their algorithms, which personalise and can amplify harmful content. A long line of reports by Select Committees and all-party groups have rightly concluded that regulation is absolutely necessary given the failure of the platforms even today to address these systemic issues. I am afraid I do not agree with the noble Baroness, Lady Bennett; being a digital native is absolutely no protection—if indeed there is such a thing as a digital native.

We will be examining the Bill and amendments proposed to it in a cross-party spirit of constructive criticism on these Benches. I hope the Government will respond likewise. The tests we will apply include: effective protections for children and vulnerable adults; transparency of systems and power for Ofcom to get to grips with the algorithms underlying them; that regulation is practical and privacy protecting; that online behaviour is treated on all fours with offline; and that there is a limitation of powers of the Secretary of State. We recognise the theme which has come through very strongly today: the importance of media literacy.

Given that there is, as a result of the changes to the Bill, increased emphasis on illegal content, we welcome the new offences, recommended in the main by the Law Commission, such as hate and communication crimes. We welcome Zach’s law, against sending flashing images or “epilepsy trolling”, as it is called, campaigned for by the Epilepsy Society, which is now in Clause 164 of the Bill. We welcome too the proposal to make an offence of encouraging self-harm. I hope that more is to come along the lines requested by my noble friend Lady Parminter.

There are many other forms of behaviour which are not and will not be illegal, and which may, according to terms of service, be entirely legal, but are in fact harmful. The terms of service of a platform acquire great importance as a result of these changes. Without “legal but harmful” regulation, platforms’ terms of service may not reflect the risks to adults on that service, and I was delighted to hear what the noble Baroness, Lady Stowell, had to say on this. That is why there must be a duty on platforms to undertake and publish risk and impact assessments on the outcomes of their terms of service and the use of their user empowerment tools, so that Ofcom can clearly evaluate the impact of their design and insist on changes or adherence to terms of service, issue revised codes or argue for more powers as necessary, for all the reasons set out by the noble Baroness, Lady Gohir, and my noble friend Lady Parminter.

The provisions around user empowerment tools have now become of the utmost importance as a result of these changes. However, as Carnegie, the Antisemitism Policy Trust, and many noble Lords today have said, these should be on by default to protect those suffering from poor mental health or who might lack faculty to turn them on.

Time is short today, so I can give only a snapshot of where else we on these Benches—and those on others, I hope—will be focusing in Committee. The current wording around “content of democratic importance” and “journalistic content” creates a lack of clarity for moderation processes. As recommended by the Joint Committee, these definitions should be replaced with a single statutory requirement to protect content where there are reasonable grounds to believe it will be in the public interest, as supported by the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

There has been a considerable amount of focus on children today, and there are a number of amendments that have clearly gained a huge amount of support around the House, and from the Children’s Charities’ Coalition on Internet Safety. They were so well articulated by the noble Baroness, Lady Kidron. I will not adumbrate them, but they include that children’s harms should be specified in the Bill, that we should include reference to the UN convention, and that there should be provisions to prevent online grooming. Particularly in the light of what we heard this week, we absolutely support those campaigning to ensure that the Bill provides for coroners to have access to children’s social media accounts after their deaths. We want to see Minister Scully’s promise to look at this translate into a firm government amendment.

We also need to expressly future-proof the Bill. It is not at all clear whether the Bill will be adequate to regulate and keep safe children in the metaverse. One has only to read the recent Institution of Engineering and Technology report, Safeguarding the Metaverse, and the report of the online CSA covert intelligence team, to realise that it is a real problem. We really need to make sure that we get the Bill right from this point of view.

As far as pornography is concerned, if we needed any more convincing of the issues surrounding children’s access to pornography, the recent research by the Children’s Commissioner, mentioned by several noble Lords, is the absolute clincher. It underlines the importance of the concerns of the coalition of charities, the noble Lord, Lord Bethell, and many other speakers today, who believe that the Online Safety Bill does not go far enough to prevent children accessing harmful pornographic content. We look forward to debating those amendments when they are put forward by the noble Lord, Lord Bethell.

We need to move swiftly on Part 5 in particular. The call to have a clear time limit to bring it in within six months of the Bill becoming law is an absolutely reasonable and essential demand.

We need to enshrine age-assurance principles in the Bill. The Minister is very well aware of issues relating to the Secretary of State’s powers. They have been mentioned by a number of noble Lords, and we need to get them right. Some can be mitigated by further and better parliamentary scrutiny, but many should simply be omitted from the Bill.

As has been mentioned by a number of noble Lords, there is huge regret around media literacy. We need to ensure that there is a whole-of-government approach to media literacy, with specific objectives set for not only Ofcom but the Government itself. I am sure that the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, will be talking about an independent ombudsman.

End-to-end encryption has also come up; of course, that needs protecting. Clause 110 on the requirement by Ofcom to use accredited technology could lead to a requirement for continual surveillance. We need to correct that as well.

There is a lot in the Bill. We need to debate and tackle the issue of misinformation in due course, but this may not be the Bill for it. There are issues around what we know about the solutions to misinformation and disinformation and the operation of algorithmic amplification.

The code for violence against women and girls has been mentioned. I look forward to debating that and making sure that Ofcom has the power and the duty to produce a code which will protect women and girls against that kind of abuse online. We will no doubt consider criminal sanctions against senior managers as well. A Joint Committee, modelled on the Joint Committee on Human Rights, to ensure that the Bill is future-proofed along the lines that the noble Lords, Lord Inglewood and Lord Balfe, talked about is highly desirable.

The Minister was very clear in his opening remarks about what amendments he intends to table in Committee. I hope that he has others under consideration and that he will be in listening mode with regard to the changes that the House has said it wants to see today. Subject to getting the Bill in the right shape, these Benches are very keen to see early implementation of its provisions.

I hope that the Ofcom implementation road map will be revised, and that the Minister can say something about that. It is clearly the desire of noble Lords all around the House to improve the Bill, but we also want to see it safely through the House so that the long-delayed implementation can start.

This Bill is almost certainly not going to be the last word on the subject, as the noble Baroness, Lady Merron, very clearly said at the beginning of this debate, but it is a vital start. I am glad to say that today we have started in a very effective way.

Tackling the Harms in the Metaverse

I recentlty took part in a session entitled Regulation and Policing of Harm in the Metaverse as part of a Society for Computers and the Law and Queen Mary University of London policy forum on the metaverse alongside Benson Egwuonwu from DAC Beechcroft and Professor Julia Hornle Chair of Internet Law at the Centre for Commercial Law Studies at Queen Mary

This is what i said in my introduction.

This is what two recent adverts from Meta said:

- “In the metaverse farmers will optimize crop yields with real time data”

- “In the metaverse students will learn astronomy by orbiting Saturn’s rings”

Both end with the message “The metaverse may be virtual but the impact is real”.

This is an important message but the first advert is a rather baffling use of the metaverse, the second could be quite exciting. Both adverts are designed to make us think about the opportunities presented by it.

But as we all know, alongside the opportunities there are always risks. It is very true of Artificial Intelligence, a subject I speak on regularly, but particularly as regards the metaverse.

The metaverse opens new forms and means of visualisation and communication but I don’t believe that there is yet a proper recognition that the metaverse in the form of immersive games which use avatars and metaverse chat rooms can cause harm or of the potential extent of that harm.

I suspect this could be because although we now recognize that there are harms in the Online world, the virtual world is even further away from reality and we again have a pattern repeating itself. At first we don’t recognize the potential harms that a new and developing technology such as this presents until confronted with the stark consequences.

The example of the tragic death of Molly Russell in relation to the understanding of harm on social media springs to mind

So in the face of that lack of recognition it’s really important to understand the nature of this potential harm, how can it be addressed and prevent what might become the normalisation of harm in the metaverse

The Sunday Times in a piece earlier this year on Metaverse Harms rather luridly headlined “My journey into the metaverse — already a home to sex predators” asserted: “....academics, VR experts and children’s charities say it is already a poorly regulated “Wild West” and “a tragedy waiting to happen” with legislation and safeguards woefully behind the technology. It is a place where adults and children, using their real voices, are able to mingle freely and chat, their headsets obscuring their activities from those around them.”

It went on: “Its immersive nature makes children particularly vulnerable, according to the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) charity.”

This is supported by the Center for Countering Digital Hate’s investigation last year into Facebook’s VR metaverse which found children exposed to sexual content, bullying and threats of violence.

And there are other potential and actual harms too not involving children. Women and girls report being harassed and sexually assaulted, there is also fraudulent activity and racial abuse.

It is clear that because of the very nature of the metaverse- the impact of its hyper-realistic environment -there are specific and distinct harms the metaverse can cause that are different from other online platforms.

These include harms that may as yet be unquantified – which makes regulation difficult. There is insufficient knowledge and understanding about harms such as the potentially addictive impact of the metaverse & other behavioural and cognitive effects it may have.

Policy and enforcement are made more difficult by fact that the metaverse is intended to allow real-time conversations. Inadequate data storage of activity on the metaverse could mean a lack of evidence to prove harm and the track of perpetrators but in turn this also raises conflicting privacy questions.

So What does the Online Safety Bill do?

It is important that metaverse is included within the platform responsibilities proposed by the bill. The Focus of the bill is about systems and risk assessment relating to published content but metaverse platforms are about activity happening in real-time and we need to appreciate and deal with this difference. It also shows the importance of having a future proofing mechanism within the bill but one that is not reliant on the decision of the Secretary of State for Culture Media and Sport.

There is the question whether the metaverse definition of regulated services currently falls within scope. This was raised by my colleagues in the Commons and ministerial reassurance was given in relation to childrten but we have had two Ministerial changes since then!

Architects of the Bill such as CarnegieUK are optimistic that the metaverse – and the tech companies who create it will not escape regulation in the UK because of the way that user generated content is defined in clause 50 and the reference there to “encountered”.

It is very likely that harms to children in the metaverse on these services will be caught.

As regards adults however the OSB now very much focuses on harmful illegal content. Query whether it will or should capture analogous crimes within the metaverse so for instance is ‘virtual rape and sexual assault’ considered criminal in the metaverse?

As regards content outside this, the current changes which have been announced to the bill which focus on Terms of Service rather than ‘legal but harmful’ create uncertainty.

It seems the idea is to give power to users to exclude other participants who are causing or threantening but how is this practical in the context of the virtual reality of the metaverse?

A better approach might be to clearly regulate to drive Safety by Design. Given the difficulties which will be encountered in policing and enforcement I believe the emphasis needs to be placed on design of metaverse platforms and consider at the very outset how platform design contributes to harm or delivers safety.

Furthermore at present there is no proper independent complaints or redress mechanism such as an Ombudsman proposed for any of these platforms which in the view of many is a gaping hole in the governance of social media which includes the metaverse.

In a recent report The Center for Countering Digital Hate recorded 100 potential violations of Meta’s policies in 11 hours on Facebook’s VR chat . CCDH researchers found that users, including minors, are exposed to abusive behaviour every seven minutes. Yet the evidence is also that Meta is already unresponsive to reports of abuse. It seems that of those 100 potential violations, only 51 met Facebook’s criteria for reporting offending content, as the platform rejects reports if it cannot match them to a username in its database.

Well we are expecting the Bill in the Lords in the early New Year . We’ll see what we can do to improve it!

Freedom of Expression Compatible with Child Protection says Lord C-J

The House of Lords recently debated the report of the Communivccations and digitl Select Committee Repotry entitled Free For All? Freedom of Expression in the Digital Age.

This is an edited version of what I said in the debate.

I congratulate the Select Committee on yet another excellent report relating to digital issues It really has stimulated some profound and thoughtful speeches from all around the House. This is an overdue debate.

As someone who sat on the Joint Committee on the draft Online Safety Bill, I very much see the committee’s recommendations in the frame of the discussions we had in our Joint Committee. It is no coincidence that many of the Select Committee’s recommendations are so closely aligned with those of the Joint Committee, because the Joint Committee took a great deal of inspiration from this very report—I shall mention some of that as we go along.

By way of preface, as both a liberal and a Liberal, I still take inspiration from JS Mill and his harm principle, set out in On Liberty in 1859. I believe that it is still valid and that it is a concept which helps us to understand and qualify freedom of speech and expression. Of course, we see Article 10 of the ECHR enshrining and giving the legal underpinning for freedom of expression, which is not unqualified, as I hope we all understand.

There are many common recommendations in both reports which relate, in the main, to the Online Safety Bill—we can talk about competition in a moment. One absolutely key point made during the debate was the need for much greater clarity on age assurance and age verification. It is the friend, not the enemy, of free speech.

The reports described the need for co-operation between regulators in order to protect users. On safety by design, both reports acknowledged that the online safety regime is not essentially about content moderation; the key is for platforms to consider the impact of platform design and their business models. Both reports emphasised the importance of platform transparency. Law enforcement was very heavily underlined as well. Both reports stressed the need for an independent complaints appeals system. Of course, we heard from all around the House today the importance of media literacy, digital literacy and digital resilience. Digital citizenship is a useful concept which encapsulates a great deal of what has been discussed today.

The bottom line of both committees was that the Secretary of State’s powers in the Bill are too broad, with too much intrusion by the Executive and Parliament into the work of the independent regulator and, of course, as I shall discuss in a minute, the “legal but harmful” aspects of the Bill. The Secretary of State’s powers to direct Ofcom on the detail of its work should be removed for all reasons except national security.

A crucial aspect addressed by both committees related to providing an alternative to the Secretary of State for future-proofing the legislation. The digital landscape is changing at a rapid pace—even in 2025 it may look entirely different. The recommendation—initially by the Communications and Digital Committee—for a Joint Committee to scrutinise the work of the digital regulators and statutory instruments on digital regulation, and generally to look at the digital landscape, were enthusiastically taken up by the Joint Committee.

The committee had a wider remit in many respects in terms of media plurality. I was interested to hear around the House support for this and a desire to see the DMU in place as soon as possible and for it to be given those ex-ante powers.

Crucially, both committees raised fundamental issues about the regulation of legal but harmful content, which has taken up some of the debate today, and the potential impact on freedom of expression. However, both committees agreed that the criminal law should be the starting point for regulation of potentially harmful online activity. Both agreed that sufficiently harmful content should be criminalised along the lines, for instance, suggested by the Law Commission for communication and hate crimes, especially given that there is now a requirement of intent to harm.

Under the new Bill, category 1 services have to consider harm to adults when applying the regime. Clause 54, which is essentially the successor to Clause 11 of the draft Bill, defines content that is harmful to adults as that

“of a kind which presents a material risk of significant harm to an appreciable number of adults in the United Kingdom.”

Crucially, Clause 54 leaves it to the Secretary of State to set in regulations what is actually considered priority content that is harmful to adults.

The Communications and Digital Committee thought that legal but harmful content should be addressed through regulation of platform design, digital citizenship and education. However, many organisations argue especially in the light of the Molly Russell inquest and the need to protect vulnerable adults, that we should retain Clause 54 but that the description of harms covered should be set out in the Bill.

Our Joint Committee said, and I still believe that this is the way forward:

“We recommend that it is replaced by a statutory requirement on providers to have in place proportionate systems and processes to identify and mitigate reasonably foreseeable risks of harm arising from regulated activities defined under the Bill”, but that

“These definitions should reference specific areas of law that are recognised in the offline world, or are specifically recognised as legitimate grounds for interference in freedom of expression.”

We set out a list which is a great deal more detailed than that provided on 7 July by the Secretary of State. I believe that this could form the basis of a new clause. As my noble friend Lord Allan said, this would mean that content moderation would not be at the sole discretion of the platforms. The noble Lord, Lord Vaizey, stressed that we need regulation.

We also diverged from the committee over the definition of journalistic content and over the recognised news publisher exemption, and so on, which I do not have time to go into but which will be relevant when the Bill comes to the House. But we are absolutely agreed that regulation of social media must respect the rights to privacy and freedom of expression of people who use it legally and responsibly. That does not mean a laissez-faire approach. Bullying and abuse prevent people expressing themselves freely and must be stamped out. But the Government’s proposals are still far too broad and vague about legal content that may be harmful to adults. We must get it right. I hope the Government will change their approach: we do not quite know. I have not trawled through every amendment that they are proposing in the Commons, but I very much hope that they will adopt this approach, which will get many more people behind the legal but harmful aspects.

That said, it is crucial that the Bill comes forward to this House. Lord Gilbert, pointed to the Molly Russell inquest and the evidence of Ian Russell, which was very moving about the damage being wrought by the operation of algorithms on social media pushing self-harm and suicide content. I echo what the noble Lord said: that the internet experience should be positive and enriching. I very much hope the Minister will come up with a timetable today for the introduction of the Online Safety Bill.

At last... compensation for Hep C blood victims

Finally after 5 decades Haemophiliac victims of the contaminted Hepatitisis C blood scandal are due to receive compensation as a result of the recommendation of the Langstaff Enquiry ...although not their familes.

Something that successive governments of all parties have failed to do.

It reminds me that TWENTY YEARS AGO when I was the Lib Dem Health Spokesperson in the Lords we were arging for an enquiry and compensation from the Blair Government. Only now 2 decades later has it become a reality.

This is what I said at the time in a debate in April 2001 initiated by the late Lord Alf Morris, that great campaigner for the disabled, asking the government : "What further help they are considering for people who were infected with hepatitis C by contaminated National Health Service blood products and the dependants of those who have since died in consequence of their infection."

My Lords, I believe that the House should heartily thank the noble Lord, Lord Morris, for raising this issue yet again. It is unfortunate that I should have to congratulate the noble Lord on his dogged persistence in raising this issue time and time again. I can remember at least two previous debates this time last year and another in 1998. I remember innumerable Starred Questions on the subject, and yet the noble Lord must reiterate the same issues and points time and time again in debate. It is extremely disappointing that tonight we hold yet another debate to point out the problems faced by the haemophilia community as a result of the infected blood products with which the noble Lord has so cogently dealt tonight.

Many of us are only too well acquainted with the consequences of infected blood products which have affected over 4,000 people with haemophilia. We know that as a consequence up to 80 per cent of those infected will develop chronic liver disease; 25 per cent risk developing cirrhosis of the liver; and that between one and five per cent risk developing liver cancer. Those are appalling consequences.

Those who have hepatitis C have difficulty in obtaining life assurance. We know that they have reduced incomes as a result of giving up work, wholly or partially, and that they incur costs due to special dietary regimes that they must follow. We also know that the education of many young people who have been infected by these blood products has been adversely affected. The noble Lord, Lord Morris, was very eloquent in describing the discrimination faced by some of them at work, in school and in society, and their fears for the future. He referred to the lack of counselling support and the general inadequacy of support services for members of the haemophilia community who have been infected in this way.

There are three major, yet reasonable, demands made by the haemophilia community in its campaign for just treatment by the Government. To date, the

Department of Health appears to have resisted stoically all three demands. First, there is the lack of availability on a general basis of recombinant genetically-engineered blood products. Currently, they are available for all adults in Scotland and Wales but not in England and Northern Ireland. Do we have to see the emergence of a black market or cross-border trade in these recombinant products? Should not the Government make a positive commitment to provide these recombinant factor products for all adults in the United Kingdom wherever they live? Quite apart from that, what are the Government doing to ensure that the serious shortage of these products is overcome? In many ways that is as serious as the lack of universal availability. Those who are entitled to them find it difficult to get hold of them in the first place.

The second reasonable demand of the campaign is for adequate compensation. The contrast with the HIV/AIDS situation could not be more stark. The noble Lord, Lord Morris, referred to the setting up of the Macfarlane Trust which was given £90 million as a result of his campaigning in 1989. The trust has provided compensation to people with haemophilia who contracted HIV through contaminated blood products. But there is no equivalent provision for those who have contracted hepatitis C. The Government, in complete contrast to their stance on AIDS/HIV, have continued to reiterate that compensation will not be forthcoming. The Minister of State for Health, Mr Denham, said some time ago that at the end of the day the Government had concluded that haemophiliacs infected with hepatitis C should not receive special payments. On 29th March of this year the noble Lord, Lord Hunt, in response to a Starred Question tabled by the noble Lord, Lord Morris, said:

"The position is clear and has been stated policy by successive governments. It is that, in general, compensation is paid only where legal liability can be established. Compensation is therefore paid when it can be shown that a duty of care is owed by the NHS body; that there has been negligence; that there has been harm; and that the harm was caused by the negligence".—[Oficial Report, 29/3/01; col. 410.]

The Minister said something very similar on 26th March. This means that the Government have refused to regard a hepatitis C infection as a special case despite the way in which they have treated AIDS/HIV sufferers who, after all, were adjudged to be a special circumstance. These are very similar situations.

In our previous debate on this, noble Lords referred to the similarity between the viral infections. They are transmitted to haemophiliacs in exactly the same manner; they lead to debilitating illness, often followed by a lingering, painful death. I could consider at length the similarities between the two viral infections and the side effects; for example, those affected falling into the poverty trap. We have raised those matters in debate before and the Government are wholly aware of the similarities between the two infections.

The essence of the debate, and the reason for the anger in the haemophilia community, is the disparity in the treatment of haemophiliacs infected with HIV

and those who, in a sense, are even more unfortunate and have contracted hepatitis C. We now have the contrast with those who have a legal remedy, which was available as demonstrated in the case to which the noble Lord, Lord Morris, referred, and are covered by the Consumer Protection Act 1987. This latter case was in response to an action brought by 114 people who were infected with hepatitis by contaminated blood. The only difference between the cases that we are discussing today and the circumstances of those 114 people is the timing. Is it not serendipity that the Consumer Protection Act 1987 covers those 114 people but not those with haemophilia who are the subject of today's debate?

It is extraordinary that the Government—I have already quoted the noble Lord, Lord Hunt—take the view that it all depends on the strict legal position. Quite frankly, the issue is still a moral one, as we have debated in the past. In fact, the moral pressure should be increased when one is faced with the comparison with both that case and the HIV/AIDS compensation scheme. People with haemophilia live constantly with risk. We now have the risk of transmission of CJD/BSE. What will be the Government's attitude to that? Will they learn the lessons of the past? I hope that the Minister will give us a clear answer in that respect.

I turn to the third key demand of the campaign by the haemophilia community. Without even having had an inquiry, the NHS is asserting that no legal responsibility to people with haemophilia exists. The Government's position—that they will not provide compensation where the NHS is not at fault—falls down because that is precisely what the previous administration did in the case of those infected with HIV. An inquiry into how those with hepatitis C were infected would perhaps establish very similar circumstances.

Other countries such as France and Canada have held official inquiries. Why cannot we do the same in this country? The Government's refusal to instigate a public inquiry surely fails the morality test. Surely the sequence of events which led up to what has been widely referred to as one of the greatest tragedies in the history of the NHS needs to be examined with the utmost scrutiny. Why do the Government still refuse to set up an inquiry? Is it because they believe that if the inquiry reported it would demonstrate that the Government—the department—were at fault?

Doctors predict that the number of hepatitis C cases among both haemophiliacs and the general population is set to rise considerably over the next decade. The Department of Health should stop ignoring the plight of this group. They should start to treat it fairly and accede to its reasonable demands. The Government's attitude to date has been disappointing to say the least. This debate is another opportunity for them to redeem themselves.